- SPEECH

COVID-19 and monetary policy: Reinforcing prevailing challenges

Speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at The Bank of Finland Monetary Policy webinar: New Challenges to Monetary Policy Strategies

Frankfurt am Main, 24 November 2020

The pandemic has tested many parts of our societies and economies in ways we had never expected. Nine months into one of the most severe crises since World War II, we are still in the early stages of understanding the pandemic’s full ramifications.

Some sectors of our economies may never return to their previous size. New business models are being developed. Inequality is rising, both within and across countries.[1] And global value chains are being re-examined.

History unambiguously suggests that the crisis is likely to fundamentally reshape the way our economies operate. Ultimately, these shifts may also affect the conduct of monetary policy. Central banks may have to change how they pursue their mandates in the face of evolving consumer preferences and changing technologies.

Predicting the direction and scope of these shifts for monetary policy is inherently difficult. Yet, the inability to predict is no excuse for not preparing for future contingencies. At the ECB, we are doing this as part of our ongoing monetary policy strategy review.[2]

My remarks today will not in any way pre-empt the Governing Council’s ongoing discussions. Instead, what I would like to offer today is a way of thinking about how the pandemic is likely to reinforce three key challenges facing central banks: how we should think about price stability when inflation is low, how monetary policy affects output and prices in the vicinity of the effective lower bound, and how we design and calibrate our instruments.

COVID-19 and risks to price stability

Let me explain each of these challenges in turn, starting with the meaning of price stability in times of low inflation.

In 2003, when the Governing Council conducted the last review of its monetary policy strategy, it defined price stability as being consistent with consumer price inflation of “below, but close to, 2% over the medium term”. It agreed on this definition after a long period in which too high rather than too low inflation was the main predicament central banks were facing.

Over the past few years, however, inflation has fallen short of our aim. Since 2014, it has averaged just 0.8% (see slide 2). Inflation has fallen short of target in other advanced economies too.

Slide 2

Secular decline in euro area inflation reinforced by pandemic

Low inflation can be the outcome of favourable economic developments. Globalisation, for example, together with significant advances in the way manufactured goods are produced, has made many consumer goods cheaper over time.

But if prices fall or stagnate for the wrong reasons, as is the case today, then they are typically the harbinger of lower future growth and employment. An economy paralysed by the pandemic has pushed underlying inflation – the rate of price change of less volatile goods and services – to a new historical low of 0.2% in October (see slide 2).

Some of these price developments may prove temporary as the economy recovers from the crisis. But the pandemic is only the latest in a series of adverse disinflationary shocks that have hit advanced economies in recent years.

Empirical evidence, for example, points to the ongoing demographic change having a persistent disinflationary impact in the euro area and other advanced economies (see left chart slide 3).[3] A longer life expectancy can induce people to save more to smooth consumption over a longer period of time.

Slide 3

Ageing society and lower productivity growth weighing on real equilibrium rate

The parallel decline in trend productivity growth since the 1970s is likely to have added to price stagnation. Higher output per hour is a necessary precondition for higher sustainable wages, incomes and, ultimately, prices.

The same forces that are weighing on inflation have also contributed to the decline in the real natural rate of interest – the rate that balances savings and investment without exerting pressure on prices (see right chart slide 3).

A lower equilibrium rate means that central banks have to find new instruments that can provide policy accommodation in the vicinity of the effective lower bound. It has made monetary policy more complex and has increased both the probability and duration of lower bound episodes.

Central banks cannot fundamentally change the long-run course of our economies. But they can, and should, make sure that the operationalisation of their mandates – the way they define and pursue price stability – leaves no doubt that too low inflation is as much a concern to society as too high inflation.

This is all the more important in a currency union as large and diverse as the euro area, where too low area-wide inflation carries substantial risks that parts of the currency area potentially face long periods of falling prices.

The euro area sovereign debt crisis has painfully demonstrated that such conditions can shift a disproportionate share of the macroeconomic adjustment burden onto workers, either through falling nominal wages or higher unemployment when wages are too sticky to adjust.

Central banks can cater for such risks in their monetary policy frameworks by acting with the same determination to downward and upward deviations from their inflation aims. This is why we are already today stressing our commitment to symmetry in our introductory statements summarising our monetary policy decisions.

The effectiveness of monetary policy in a low rate environment

When the pandemic broke out in late February, we honoured this commitment by reacting forcefully to the rapidly emerging downside risks to price stability.

The pandemic emergency purchase programme, or PEPP, has been at the heart of our policy response.[4] By stabilising market conditions at a time of exceptional uncertainty and demand for safety, the PEPP acted as an important circuit breaker that stopped the pandemic from turning into a full-blown financial crisis (see slide 4).

Slide 4

PEPP highly effective in stabilising financial markets

In doing so, it saved millions of jobs and businesses. Its strong impact on the economy was in line with a rich literature that suggests that monetary policy is most effective during periods of market turmoil or when the economy is in a severe recession.[5]

In these circumstances, a tightening of financial conditions damages the economy more severely due to a negative multiplier effect (see left chart slide 5). Monetary policy that acts to offset a tightening in financial conditions is then highly effective.

Slide 5

Monetary policy most effective in stressed conditions, deposit rates often floored at 0%

But empirical evidence also suggests that the marginal effects of financial conditions on output and inflation become less clear when the economy is recovering or expanding.[6]

It is likely that this state-contingent effectiveness of monetary policy is also at play in current times.

Although recent news on the effectiveness of vaccines provides light at the end of the tunnel, significant uncertainty about future income prospects can be expected to prevail for some time, also because the pace of the rollout of vaccines and their acceptance among the public remain uncertain.

Heightened uncertainty, in turn, is likely to weaken the willingness and ability of firms and households to take full advantage of historically loose financial conditions.[7]

In these situations, monetary policy cannot unfold its full potential. Fiscal expansion is then indispensable in order to sustain demand and mitigate the long-term costs of the crisis.

The debate on the appropriate policy mix, however, predates the pandemic.

In the years after the global financial and euro area sovereign debt crises, there has been a broad debate about the appropriate policy response to lift the euro area economy out of its low-growth, low-inflation trap.

An important question in this debate is whether and how monetary policy transmission changes in the vicinity of the effective lower bound, and how this might affect the interaction between monetary and fiscal policy also outside crisis times.[8]

This question goes to the very heart of monetary policymaking.

To see this, it is useful to recall the canonical New Keynesian model that most central banks use to inform their decisions. At the core of these models is the Euler equation, or the IS curve, which provides two fundamental hypotheses on which policy transmission is built.

The first is the “interest rate hypothesis” – the belief that aggregate demand reacts linearly to changes in real interest rates.

The second is the “expectations hypothesis” – the belief that expected real interest rates matter and that changes in inflation expectations have real effects.

These two cornerstones have long been taken for granted. But they are now under increasing scrutiny.

Monetary policy and the interest rate hypothesis

The interest rate hypothesis needs closer inspection on three grounds.[9]

First, an emerging literature suggests that monetary policy transmission may not be linear in the level of the interest rate.[10] In other words, the slope of the IS curve may be different when interest rates are low, or when they have been low for a protracted period of time.

Evidence is too scant to draw definitive conclusions at this stage. But such non-linearities could affect the extent to which central banks can bring future activity into the present: researchers have dubbed this the “macroeconomic reversal rate”.[11]

Second, the transmission of changes in policy rates to bank lending rates seems to weaken around the zero lower bound (see right chart slide 5).[12] All else equal, the lower the pass-through of interest rate changes to bank deposit rates, the smaller the effects of monetary policy on aggregate demand.[13]

And third, people often cannot distinguish between real and nominal developments and may therefore react less to changes in real interest rates than what our models would tend to suggest.[14] Although money illusion has long been recognised in the economics profession, it continues to be largely ignored in core central bank models.

Empirical evidence shows that money illusion affects financial decisions, particularly – but not only – those made by households, who often mistake changes in nominal interest rates for changes in real rates.[15]

Recent experience suggests that money illusion may not only change the nature of the interest rate channel, it may also expose central banks to widespread criticism. The debate on the “expropriation” of savers is a prime example.[16]

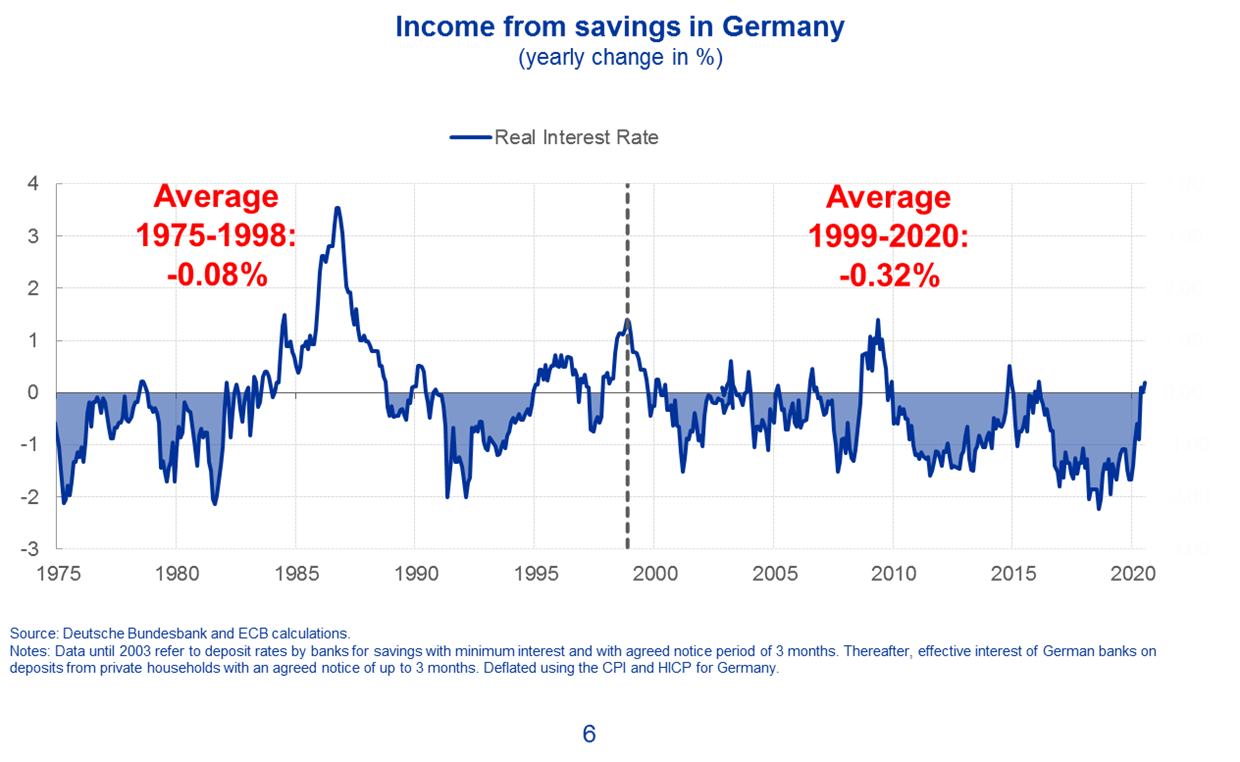

Many people may be surprised to learn that negative real interest rates are not a new phenomenon. In Germany, for example, since the euro was introduced, the average real interest rate for savings and demand deposits has been roughly the same as the average over the preceding two decades (see slide 6).

Slide 6

Negative real rates are not a new phenomenon

The expectations hypothesis

This bias in people’s perception brings me to the second hypothesis – the expectations hypothesis.

When policy space is limited, expectations become the main driver of monetary policy transmission in New Keynesian models. The idea of central banks providing forward guidance is largely built on this proposition.

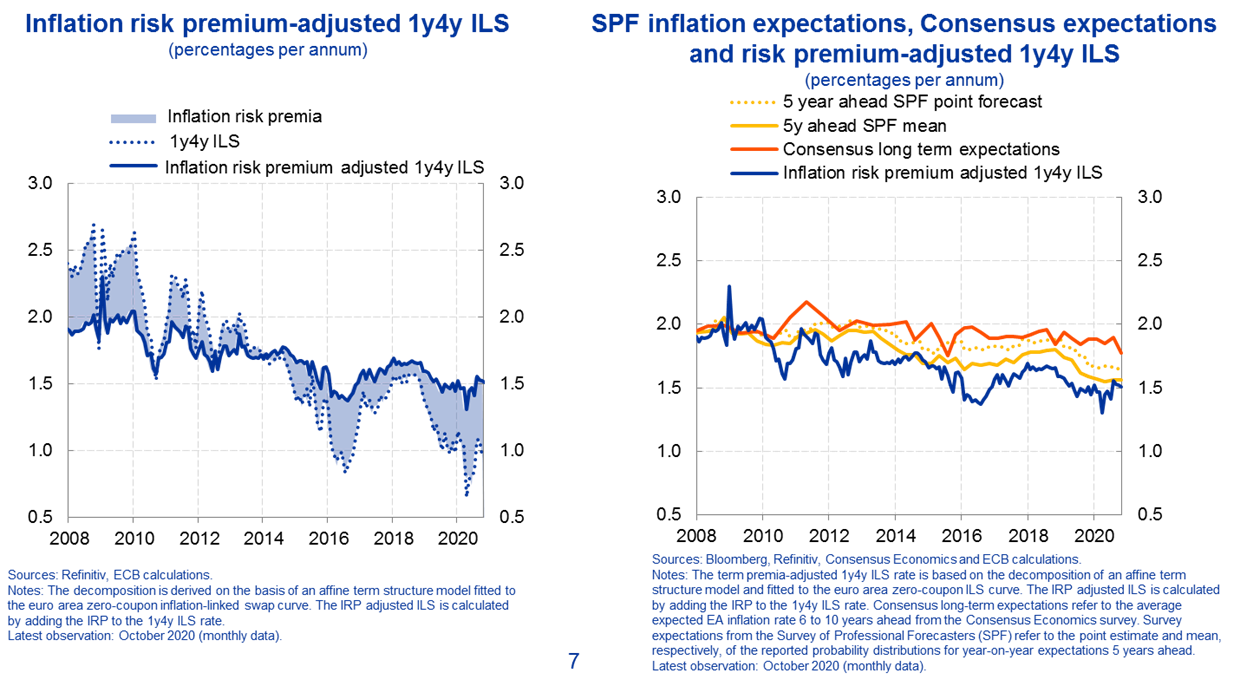

This is why many central bank scholars have been concerned about the gradual fall in market-based inflation expectations in recent years. It has raised real expected interest rates, thereby tightening financial conditions.

The extent to which these developments have weighed on aggregate demand is subject to controversy, however, for two main reasons.

First, a large part of the fall in market-based inflation expectations can be explained by a fall in the inflation risk premium (see left chart slide 7). Following years of persistently low inflation, investors no longer feel the need to protect themselves against high inflation.

Once one corrects for the fall in the risk premium, developments in market-based and survey-based measures of inflation expectations are much more aligned (see right chart slide 7).

Slide 7

Declining risk premium accounting for large share of fall in inflation expectations

Second, it is not clear how representative option prices in financial markets are for the broader economy. Empirical evidence suggests that such indicators can often provide only little additional forward-looking information about inflation, even for a horizon of only one to two years ahead.[17]

This raises the question of whether inflation expectations of households and firms may be more relevant than those of the market for shaping macroeconomic outcomes in line with the expectations hypothesis.[18]

By now, we have a relatively clear understanding that most households and firms cannot point with any certainty to the actual level of inflation or interest rates.[19] For example, in surveys a significant fraction of consumers report very high inflation expectations – often in excess of 10%.

But a limited understanding of actual levels does not necessarily stop people from acting on their beliefs. Here the evidence is more mixed.

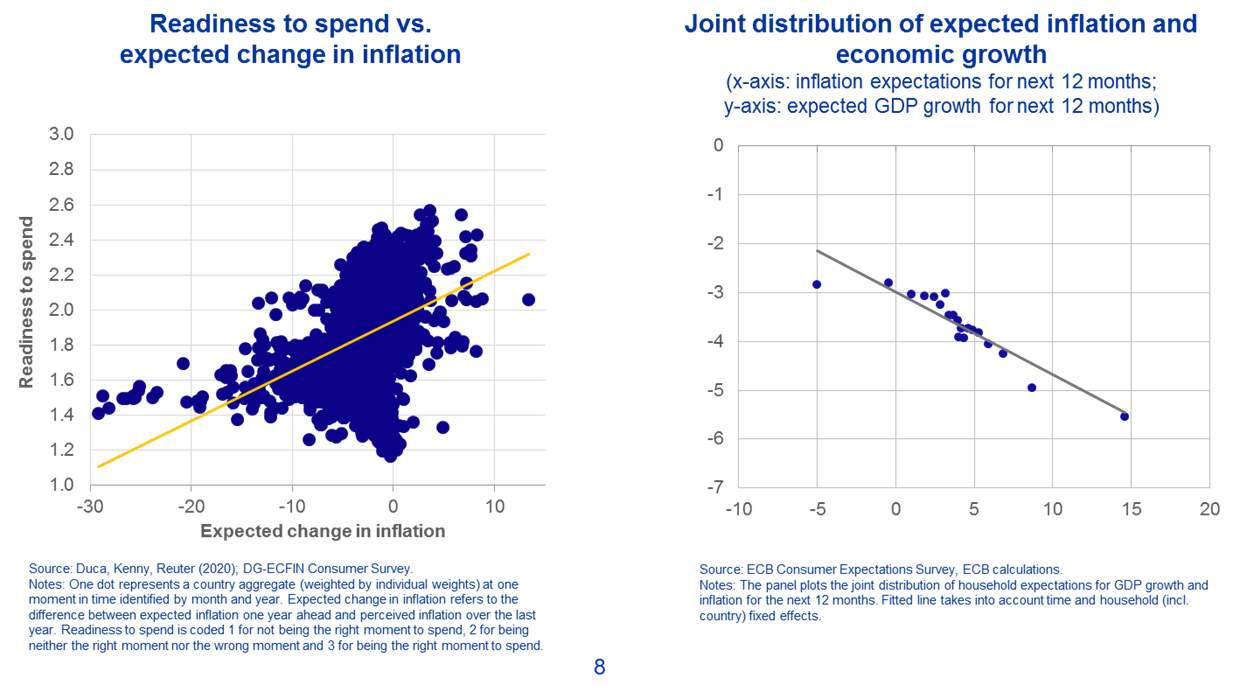

ECB research, for example, finds that people tend to spend more than they would otherwise if they expect future inflation to be higher than the perceived level today (see left chart slide 8).[20]

Slide 8

Association of higher inflation expectation with lower expected economic growth

Other studies come to different conclusions, however. They find either no evidence of inflation expectations affecting consumption decisions or, more disturbingly, even suggest that higher inflation expectations could lower – rather than raise – consumption.[21]

One interesting pattern that can help explain these findings is that rising inflation expectations often seem to go hand-in-hand with expectations of lower incomes and lower economic growth (see right chart slide 8).[22]

These findings suggest that individuals are far from being as rational and forward-looking as our canonical models assume.[23] Indeed, controlling for these insights helps resolve the infamous “forward guidance puzzle”, i.e. the phenomenon that models predict that promises to keep rates low for longer will have unrealistically large effects on the real economy.[24]

Bounded rationality may hence limit the efficacy of policies geared towards boosting inflation expectations, all the more so as new empirical evidence highlights that most households are very hesitant about adjusting their long-term inflation expectations in response to news.[25]

None of this is to say that monetary policy is powerless. On the contrary, current highly accommodative financial conditions provide a continuous and measurable support to the euro area economy. Preserving them for as long as needed will be essential to ensure that inflation returns to our aim in the medium term.

Bounded rationality and the way the interest rate channel works at the lower bound rather suggest two things.

First, fiscal policy has become more important as a macroeconomic stabilisation tool, also once we leave the pandemic behind us.

And, second, if people associate higher inflation with worse personal economic outcomes, then we should become better in explaining to the public what it is that we do and why current low inflation may be harmful to growth and employment.

Trust in the ECB remains unacceptably low and has fallen over time, also as unconventional instruments have introduced concepts and terminology that are hardly accessible to a large part of our society (see slide 9). New research demonstrates that trust has a tangible impact on households’ inflation expectations.[26]

Slide 9

Declining trust in ECB could affect inflation expectations and hamper monetary policy

The narrow mandate of the ECB compared with that of other major central banks arguably makes this mission even more complicated from a communication perspective: although there is often a “divine coincidence” between stable prices and employment, our actions ultimately have to be rooted in our primary mandate.

We know that people – once inflation is low – care more about employment, which is part of the US Federal Reserve’s mandate. But it is much harder to explain why inflation of 2% is better than 1%.

Low inflation and the design and calibration of policy instruments

A much broader communication strategy that goes well beyond financial market participants will therefore be an important element in reinforcing the effectiveness of monetary policy.

But what we learn from our analysis of how monetary policy transmission to the real economy may change in a low interest rate environment may ultimately also affect the way we calibrate and design our policy instruments, as well the horizon over which we want to achieve our inflation aim.

In principle, central banks facing lower expected gains from easing monetary policy further in an environment of highly accommodative financial conditions could double down on their efforts to compensate for the loss in efficacy.

They would face two pertinent challenges, however.

The first is that monetary policy faces constraints. For example, we may not know precisely where the effective lower bound lies, but we know that there is one.

Exempting a portion of excess reserves from negative rates, or rewarding lending activities at rates below our main policy rate, have been effective instruments in stretching our boundaries. But these instruments will ultimately also face constraints.

The second challenge relates to the unintended side effects of monetary policy.

The wide-ranging nature of the instruments we use today raises the bar of accountability. But side effects are a difficult topic for central banks, no less than for medical practitioners. The evidence on side effects is often inconclusive, before it is too late.

Money illusion, for example, may push house prices increasingly away from fundamentals, despite real interest rates not being extraordinarily low.[27]

Banks may start restricting their lending activities the lower yields are and the flatter the yield curve is, particularly in an environment in which capital buffers may need rebuilding following the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis.[28]

And the larger the share of bonds that we purchase, the higher the risk that market liquidity may deteriorate over time.

These concerns raise the question as to whether monetary policy should take financial stability considerations more systematically into account and, if so, how this should be done.

One aspect in this context is the optimal interaction between monetary and prudential policies. While macroprudential policies are the first line of defence against the build-up of financial vulnerabilities, it is widely acknowledged that such policies do not yet offer effective protection.[29]

A second aspect relates to how a more effective integration of asset price developments into the monetary policy framework could better reflect the role of financial stability in preserving price stability over the medium term. The pandemic is the latest in a series of shocks that vividly demonstrate how financial factors may amplify real shocks, giving rise to huge costs for society as a whole.

A third and complementary aspect is the horizon over which we want to bring inflation back to our aim.

If shocks to aggregate demand, such as those seen during the pandemic, reinforce downward pressure on prices from long-lasting structural factors, and if the inflation expectations of firms and households are less sensitive than widely assumed, then it could be optimal to lengthen the “medium term” when monetary policy is already highly accommodative.[30]

By accepting a somewhat slower return of inflation towards their aim, and by focusing more on the duration of policy support, central banks may effectively mitigate potential risks to financial stability arising from a more intense usage of their policy instruments in the pursuit of their mandate.

A more elastic use of the “medium term” notion might be all the more conducive in an environment in which a high degree of prevailing uncertainty is likely to considerably increase the lags with which policy is transmitted to the real economy.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The pandemic hit the global economy at a time when far-reaching secular changes had already prompted central banks to reflect on the appropriateness of their monetary policy frameworks. COVID-19 has reinforced many of the challenges posed by these changes.

In the euro area, the coincidence of a protracted period of low inflation, sluggish potential growth and highly accommodative financial conditions raises important questions as to how the Governing Council should interpret its mandate and how it should conduct and communicate its operations in a way that credibly conveys its strong commitment to achieving price stability while minimising any adverse consequences of its policies for society.

These questions form important elements of our monetary policy strategy review. The outcome will be a framework that reflects our understanding of how the economy has changed since we conducted our last strategy review and ensures that monetary policy will continue to faithfully serve the people of Europe.

Thank you.

- Schnabel, I. (2020), “Unequal scars – distributional consequences of the pandemic”, speech at the panel discussion “Verteilung der Lasten der Pandemie” (“Sharing the burden of the pandemic”), Deutscher Juristentag 2020.

- Lagarde, C. (2020), “The monetary policy strategy review: some preliminary considerations”, speech at the “ECB and Its Watchers XXI” conference, Frankfurt am Main, 30 September.

- Bobeica et al. (2017), “Demographics and inflation”, ECB Working Paper No 2006.

- For a more detailed account of the ECB’s policy response to the COVID-19 crisis, see Schnabel, I. (2020), “The ECB’s policy in the COVID-19 crisis – a medium-term perspective”, remarks at an online seminar hosted by the Florence School of Banking & Finance, 10 June.

- Jannsen, N., Potjagailo, G. and Wolters, M.H. (2019), “Monetary Policy during Financial Crises: Is the Transmission Mechanism Impaired?”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 15, No 4, pp. 81-126; Dahlhaus, T. (2017), “Conventional Monetary Policy Transmission During Financial Crises: An Empirical Analysis”, Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 32, No 2, pp. 401-421; Ciccarelli, M., Maddaloni, A. and Peydro, J.L. (2013), “Heterogeneous Transmission Mechanism: Monetary Policy and Financial Fragility in the Euro Area”, Economic Policy, Vol. 28, No 75, pp. 459-512.

- Bech, M.L., Gambacorta, L. and Kharroubi, E. (2014), “Monetary Policy in a Downturn: Are Financial Crises Special?”, International Finance, Vol. 17, No 1, pp. 99-119.

- Bloom, N., Bond, S. and Van Reenen, J. (2007), “Uncertainty and Investment Dynamics”, Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 74, No 2, pp. 391-415; Bernanke, B. (1983), “Irreversibility, Uncertainty, and Cyclical Adjustment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 98, No 1, pp. 85-106.

- Schnabel, I. (2020), “Pulling together: fiscal and monetary policies in a low interest rate environment”, speech at the Interparliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance in the European Union, Frankfurt am Main, 12 October; Schnabel, I. (2020), “The shadow of fiscal dominance: Misconceptions, perceptions and perspectives”, speech at the Centre for European Reform and the Eurofi Financial Forum on “Is the current ECB monetary policy doing more harm than good and what are the alternatives?”, Berlin, 11 September.

- Schnabel, I. (2020), “Monetary policy in changing conditions”, speech at the second EBI Policy Conference on “Europe and the Covid-19 Crisis – Looking back and looking forward”, Frankfurt, 4 November.

- Van den End, J.W. et al. (2020), “Macroeconomic reversal rate: evidence from a nonlinear IS-curve”, DNB Working Papers, No 684, De Nederlandsche Bank, May; Borio, C. and Hofmann, B. (2017), “Is monetary policy less effective when interest rates are persistently low?”, BIS Working Papers, No 628, Bank for International Settlements, April. For linear estimates of the IS curve, see Holston, K., Laubach, T. and Williams, J.C. (2017), “Measuring the natural rate of interest: International trends and determinants”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 108, Supplement 1, pp. S59-S75; and Garnier, J. and Wilhelmsen, B.R. (2009), “The natural rate of interest and the output gap in the euro area: a joint estimation”, Empirical Economics, Vol. 36, No 2, pp. 297-319.

- Van den End, J.W. et al., ibid.

- Brunnermeier, M. and Koby, Y. (2018), “The Reversal Interest Rate”, NBER Working Papers, No 25406, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Darracq Pariès, M., Kok, C. and Rottner, M. (2020), “Reversal interest rate and macroprudential policy”, Working Paper Series, No 2487, ECB.

- Fisher, I. (1928), The Money Illusion, Adelphi Company, New York.

- Darriet, E. et al. (2020), “Money illusion, financial literacy and numeracy: Experimental evidence”, Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 76; Yamamori, T., Iwata, K. and Ogawa, A. (2018), “Does money illusion matter in intertemporal decision making?”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 145, pp. 465-473.

- Schnabel, I. (2020), “Narratives about the ECB’s monetary policy – reality or fiction?”, speech at the Juristische Studiengesellschaft, Karlsruhe, 11 February.

- Bauer, M.D. and McCarthy, E. (2015), “Can We Rely on Market-Based Inflation Forecasts?”, FRBSF Economic Letter, No 2015-30, Federal Reserve Bank of San Fransico; Álvarez, L.J. and Correa-López, M. (2020), “Inflation expectations in euro area Phillips curves”, Economics Letters, Vol. 195, No 109449.

- Coibion, O. and Gorodnichenko, Y. (2015), “Is the Phillips curve alive and well after all? Inflation expectations and the missing disinflation”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 7, No 1, pp. 197-232.

- Coibion, O. et al. (2020), “Forward Guidance and Household Expectations”, NBER Working Papers, No 26778, National Bureau of Economic Research; and Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y. and Weber, M. (2019), “Monetary Policy Communications and their Effects on Household Inflation Expectations”, NBER Working Papers, No 25482, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Duca-Radu, I., Kenny, G. and Reuter, A. (2020), “Inflation expectations, consumption and the lower bound: Micro evidence from a large multi-country survey”, Journal of Monetary Economics, March.

- Bachmann, R., Berg, T.O. and Sims, E.R. (2015), “Inflation expectations and readiness to spend: Cross-sectional evidence”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 7, No 1, pp. 1-35; Coibion et al. (2019), “How Does Consumption Respond to News about Inflation? Field Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial”, NBER Working Papers, No 26106, National Bureau of Economic Research; Burke, M.A. and Ozdagli, A.K. (2013), “Household Inflation Expectations and Consumer Spending: Evidence from Panel Data”, Research Department Working Papers, No 13-25, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston; Andrade, P., Gautier, E. and Mengus, E. (2020), “What Matters in Households’ Inflation Expectations?”, CEPR Discussion Paper Series, No 14905, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Candia, B., Coibion, O. and Gorodnichenko, Y. (2020), “Communication and the Beliefs of Economic Agents”, NBER Working Papers, No 27800, National Bureau of Economic Research. This effect has also been found for firms, but with varying effects depending on whether the economy is at the lower bound or not, see Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y. and Ropele, T. (2019), “Inflation Expectations and Firm Decisions: New Causal Evidence”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 135, No 1, pp. 165-219.

- Central banks have started to also consider adaptive expectations. See also Guerkaynak, R. S., Levin, A. T., Marder, A. N. and Swanson, E.T. (2007), ”Inflation targeting and the anchoring of inflation expectations in the Western Hemisphere, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Review, pp. 25-47.

- Gabaix, X. (2020), “A Behavioral New Keynesian Model”, American Economic Review, Vol. 110, No 8, pp. 2271-2327; McKay, A., Nakamura, E. and Steinsson, J. (2016), “The Power of Forward Guidance Revisited”, American Economic Review, Vol. 106, No 10, pp. 3133-3158; McKay, A., Nakamura, E. and Steinsson, J. (2017), “The Discounted Euler Equation: A Note”, Economica, Vol. 84, No 336, pp. 820-831.

- Coibion, O. et al. (2020), “Average Inflation Targeting and Household Expectations”, NBER Working Papers, No 27836, National Bureau of Economic Research; and Coibion, O. et al. (2020), “Forward Guidance and Household Expectations”, NBER Working Papers, No 26778, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Christelis et al. (forthcoming), “Trust in the Central Bank and Inflation Expectations”, International Journal of Central Banking.

- Piazzesi, M. and Schneider, M. (2007), “Inflation Illusion, Credit, and Asset Pricing”, NBER Working Papers, No 12957, National Bureau of Economic Research; ECB (2020), Financial Stability Review, May.

- Heider, F., Saidi, F. and Schepens, G. (2019), “Life below Zero: Bank Lending under Negative Policy Rates”, Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 32, No 10, pp. 3728-3761; Darracq Pariès, M. et al., op.cit.

- Adrian, T. and Liang, N. (2018), “Monetary Policy, Financial Conditions, and Financial Stability”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 14, No 1, pp. 73-131; Schnabel, I. (2020), “COVID-19 and the liquidity crisis of non-banks: Lessons for the future”, speech at the Financial Stability Conference on “Stress, Contagion, and Transmission” organised by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and the Office of Financial Research, 19 November.

- Schnabel, I. (2020), “How long is the medium term? Monetary policy in a low inflation environment”, speech at the Barclays International Monetary Policy Forum, London, 27 February.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts- 24 November 2020