- SPEECH

- Frankfurt am Main, 17 July 2020

Never waste a crisis: COVID-19, climate change and monetary policy

Speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at a virtual roundtable on “Sustainable Crisis Responses in Europe” organised by the INSPIRE research network, 17 July 2020

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic constitutes an unprecedented shock across many dimensions.

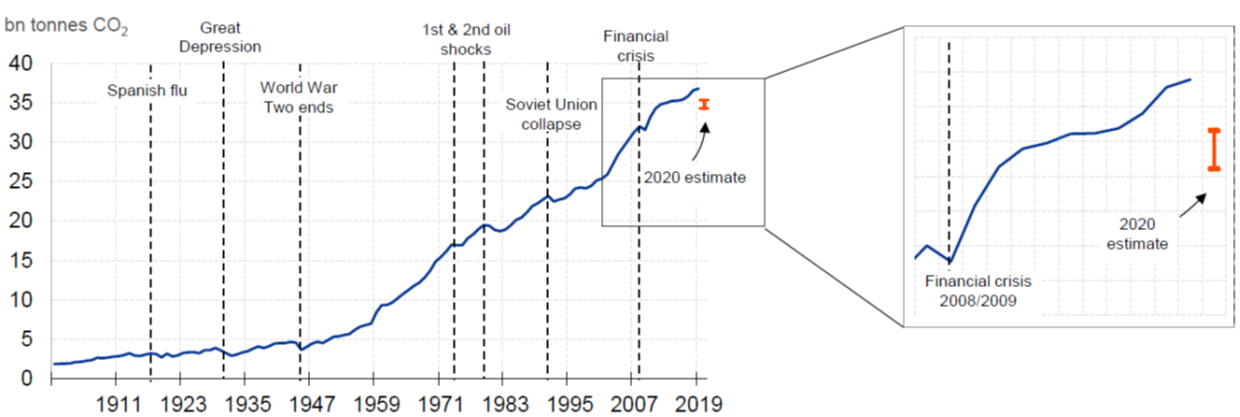

The lockdown has led to the temporary closing-down of many production sites. Global air and road travel have come to a virtual standstill. The effects have been so large and so disruptive that total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2020 will be about 4 to 7% lower than estimated before the crisis (see figure 1).[1] In the past 120 years, there has never been an event that had such a dramatic impact on global CO2 emissions.

Global annual CO2 emissions (in million tonnes)

Sources: Le Quéré et al. (2020), Global Carbon Project, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Centre (CDIAC) and UNFCCC (June 2019). The range refers to the 4-7% estimated drop in emissions in 2020.

Yet, studies show that even the substantial restrictions in production and mobility that were necessary to contain the spread of the virus would not be sufficient to limit the global temperature increase to the 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, as aspired under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

In order to meet that goal, according to the United Nations, global emissions would need to drop by 7.6% each year between 2020 and 2030.[2] Given the economic and social hardship associated with this year’s reduction, such a drop is hardly feasible by simply reducing economic activity.

The pandemic is therefore a stark reminder that preventing climate change from inflicting permanent harm on the global economy requires a fundamental structural change to our economy, inducing systematic changes in the way energy is generated and consumed.

With brutal clarity, the current crisis has exposed two major risks to the global economy: first, the far-reaching damages imposed on our society by a lack of prevention and early action, fostered by disbelief in science, in the face of a global shock that threatens not only the economy but our lives.

And, second, the repercussions of a failure to act collectively in a globalised world where inaction in one part of the globe can lead to highly disruptive and long-lasting spillover effects in other parts, hitting the poorest and most vulnerable in our societies most severely.

In this sense, the pandemic has been a warning shot with regard to the much greater challenge arising from climate change. In his famous speech, Mark Carney, then Governor of the Bank of England, has argued that “the catastrophic impacts of climate change will be felt beyond the traditional horizons of most actors – imposing a cost on future generations that the current generation has no direct incentive to fix”.[3]

Moreover, studies have uncovered a significant lag in discerning the benefits of mitigation measures,[4] which makes it much harder to impose costs on society today if measurable results are available much later.

By making the costs of a major, truly global crisis more tangible, the pandemic may help to remove the “tragedy” from Mark Carney’s horizon: after COVID-19, the dramatic consequences of a global climate crisis may be much easier to imagine. And given the need for fundamental structural change after this crisis, the willingness to use this chance to take precautions against the even bigger risk of a climate crisis may have increased.

In order to achieve the European Union’s target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, our response to the growing risks of climate change has to start with the way we rebuild our economies after the pandemic.

In my remarks this morning, I will argue that three complementary pillars are needed to accelerate the transition towards a low-carbon economy: an effective carbon price, a strong investment programme and a greener financial market.

I will also argue that central banks have a role to play in mitigating climate-related risks, even within their traditional mandates, because global warming poses severe risks to price stability.

Carbon pricing as the central tool

So let me start with the first pillar, the introduction of global carbon pricing.

Europe is already spearheading global efforts, which is essential at times when a global solution is not in sight. The EU’s emission trading system (ETS) is the world’s largest carbon market. Its “cap and trade” scheme provides a mechanism for both reducing the total amount of emissions in a cost-efficient way and ensuring that pollution is priced adequately.

A recent study shows that the ETS saved more than one billion tons of CO2 between 2008 and 2016, a 3.8% reduction in total EU-wide emissions.[5] And only this week, carbon prices hit their highest level in more than a decade, despite the sharp contraction in aggregate demand and energy consumption, possibly reflecting the anticipation of tighter climate policies under the European Green Deal (see figure 2).

EU ETS price (in euro per ton CO2 emissions)

Source: Bloomberg. Last observation: 15 July 2020. Notes: Energy Broker pricing on Bloomberg updates on a near real-time basis. Updates only occur when there is activity in the market, so there may not be updates to every contract every day.

There is no reason for complacency, however. Currently, the ETS only covers economic sectors that together account for less than half of total carbon emissions in the EU, whereas the remaining sectors are subject to a patchwork of non-harmonised measures across the European Union. A global solution is out of reach.

Moreover, carbon pricing is not a sufficient condition to manage the transition towards a more sustainable economy.

Fostering green investment and innovation

This brings me to the second pillar.

In isolation, higher carbon prices could carry the risk of households facing higher prices, without being able to switch their consumption expenditures towards greener technologies.

Strong public and private investment efforts are therefore needed to prevent consumers from being locked into carbon-intensive technologies. Public investments can serve a catalytic function in this context. Infrastructure investments, for example for charging electric vehicles, can trigger wide-ranging changes in the type of energy mix used in public and private transport.

The coronavirus crisis offers a must-seize opportunity. The costs of letting the current crisis go to waste would be exceptionally large, for two main reasons.

First, business dynamism in Europe has been comparatively weak for a long time (see figure 3). There are considerably lower shares of both growing and shrinking firms than in other advanced economies, holding back productivity growth as well as technology creation and diffusion.[6] Put simply, new firms are more likely to adopt new and greener technologies, and we are not seeing enough of them in Europe.

New business creations (thousands)

Notes: Number of new businesses created outside of agriculture (FR, DE, IT, ES), and number of business applications outside of agriculture (US), 12-months rolling average. Data for France excludes sole proprietorships. US data has been transformed from weekly to monthly, data for Italy from quarterly to monthly and data for Spain from annual to monthly. Data for Spain available only until 2018. Sources: INSEE (FR), Destatis (DE), Banca d'Italia (IT), Census Bureau (US) and INE (ES).

COVID-19 is a unique opportunity to break this vicious circle. The crisis will require a massive reallocation of capital and labour across sectors and economies. It has the potential to unleash unprecedented forces of Schumpeterian creative destruction that can help accelerate the adoption and diffusion of green and sustainable technologies across large parts of the economy.

Policymakers need to allow, facilitate and support this process. But the scope for policy mistakes has increased measurably as the crisis has forced governments to expand their role in economic activity.

There can be no doubt that a forceful fiscal response to the crisis was both necessary and adequate. Nevertheless, there is a risk that some of the measures – if kept in place for too long – may delay the necessary structural adjustments. Even before the pandemic, some carbon-intensive sectors had been facing strong secular headwinds in the wake of changing consumer preferences.

The second reason is that the crisis will cause a significant increase in the public and private debt burden. Issuance of public and corporate bonds is reaching record levels.

In a low-interest-rate environment, the increase in leverage carries a lower cost than in the past. But the best way to avoid the risk of growing debt becoming a long-lasting burden for society is to lift potential growth today and shift the economy on a higher and more sustainable growth path. There are few other areas with a comparable growth potential as green technologies.

These are the reasons why the EU Innovation Fund and the EU recovery fund’s focus on the green transition are so important. If flanked by national measures that improve the overall business environment, they will be major policy levers for transforming the European economy more fundamentally and overcoming short-termism in investment behaviour that ignores climate-related risks.

Greening financial markets

The third pillar needed to accelerate the transition towards a low-carbon economy relates to financial markets.

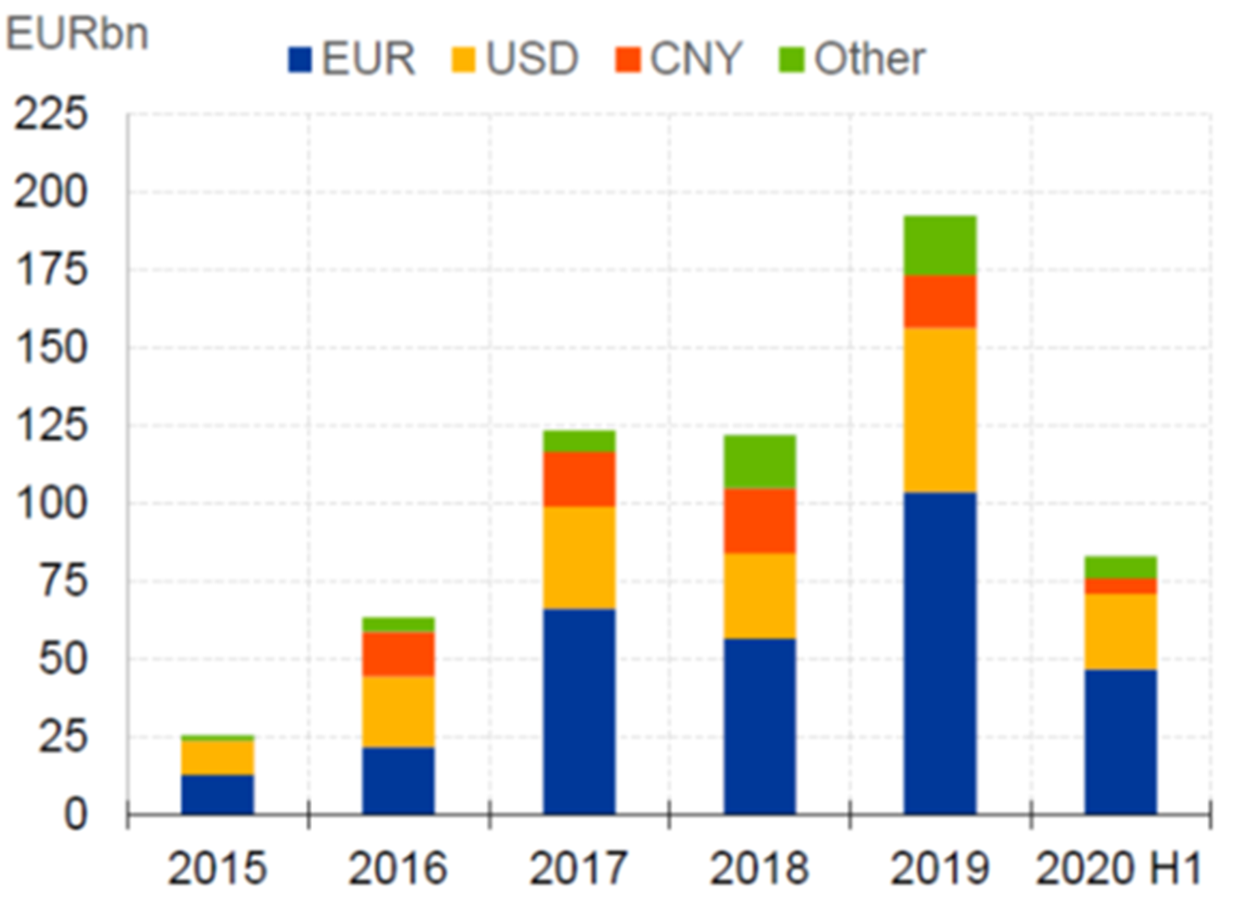

The large increase in required bond issuance in response to the pandemic offers the opportunity to deepen the green financial market. Green bond issuance has steadily increased in recent years, with a strong focus on the euro area and on public agencies and financial institutions (see figure 4).

Green bond issuance by currency of denomination

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations. Last observation: 15 July 2020

Green bond outstanding amounts by issuer type

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations. Last observation: 15 July 2020

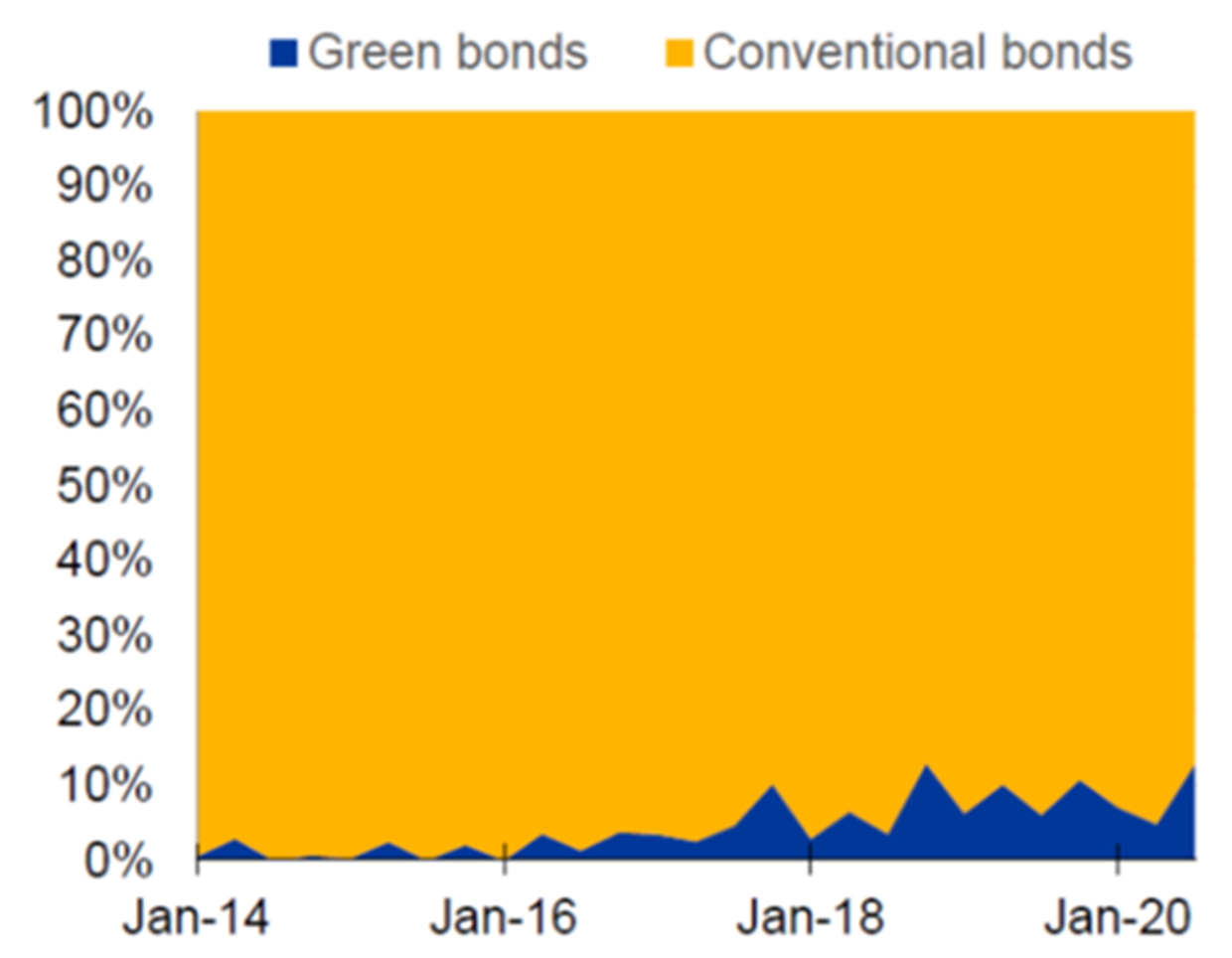

But the universe of green bonds remains vanishingly small compared with the total bond universe and in spite of the exponential surge in investor demand for green assets over the past years (see figure 5).

Share of IG green bonds in global gross issuance (in %, based on EUR data)

Source: Dealogic. Last observation: 15 July 2020.

Global developed market cumulative flows into ESG funds (USD bn)

Source: EPFR. Last observation: 15 July 2020.

The lack of market depth is also reflected in prices. There seems to be a negative relationship between the outstanding volume of green bonds and their spread over non-green peers (see figure 6).

Green bond outstanding volume in % of size of direct curve peers (x-axis) vs. premium (y-axis)

Source: Commerzbank Research.

Hence, green bonds tend to be priced at a premium over conventional bonds, in part reflecting poorer liquidity conditions. For example, the daily trading turnover of French conventional government bonds remains notably higher than that of their green counterparts (see figure 7).

Average daily bond turnover for selected French bonds(5-day moving average)

Source: Commerzbank Research.

The current crisis could give an unparalleled boost to the green financial market and thereby help reduce the costs of transitioning towards a low-carbon economy.

We have already seen firms and governments employ more diverse and creative funding strategies in recent weeks. Many euro area governments have started, or are planning, to issue green bonds for the first time.

This is undoubtedly good news. But current market forces will not be sufficient to mobilise the funds required to finance the transition towards a more sustainable economy. Further policy actions are urgently needed, primarily on two fronts.

First, the costs of the crisis are mainly debt-financed. But growing empirical evidence suggests that stock markets are more effective than bond markets in financing the greening of our economy, given the high capital intensity, high risks and long-term horizon of most projects.[7]

Europe therefore urgently needs to make faster progress towards creating a true capital markets union, with a strong focus on equity markets. Euro area equity markets remain too shallow and risk-sharing across borders too limited to lift the economy onto a more sustainable growth path.

There is also a geopolitical dimension: financial market structures are gradually readjusting after the United Kingdom’s exit from the EU. Green finance has the potential to tip the scale to one side or the other and act as a catalyst for promoting the provision of financial services more broadly throughout the euro area.

Second, faster progress is needed on disclosure and standardisation.

For markets to better support the greening of the economy, and to mitigate risks to financial stability, asset prices need to correctly reflect the externalities associated with climate change.

At the current juncture, however, financial markets are suffering from various market failures. Uncertainty about what actually qualifies as green activity is one of them. Common and clear definitions are a fundamental building block for facilitating the market pricing of environmental risks.

The adoption in mid-June of the European Commission’s taxonomy regulation was an important step in establishing a classification system for sustainable economic activities.

But three words of caution are in order.

First, the framework is expected to become fully operational only after the adoption of its delegated acts in 2021 and 2022 and so will provide limited guidance at a time when issuance needs are reaching historical levels. During this period, we need to find a way to mitigate the risks of “greenwashing” so as to channel funds to where they are most effective.

Second, a green taxonomy needs to be complemented by a taxonomy for environmentally harmful activities so that investors can identify transition risks more easily and hence also price risk differentials more effectively.[8]

And third, the taxonomy requires granular data for it to be useable. In the absence of corporate-level information, the taxonomy cannot be put into use and many metrics will prove useless.

This is clearly visible when looking at environmental ratings for financial products: if available, they are often inconsistent, incomparable and at times unreliable – in many cases reflecting the absence of granular data or the large discretion in the construction of such indicators. Indicators from different sources often display a very low correlation (see figure 8).

Financial market pricing of climate risk: correlations of bank environmental scores by Bloomberg and Refinitiv

Source: ECB Financial Stability Review, November 2019 based on Bloomberg, Refinitiv EIKON, S&P Global Market Intelligence and Dealogic. Notes: The Bloomberg and Refinitiv environmental scores give values between 0 and 100, whereby a higher value indicates a better performance in terms of environmental variables. The full unbalanced sample consists of 49 banks and 23 insurers in the EU and the United States.

Disclosure of climate-related information should therefore become mandatory and more standardised under the revised Non-Financial Reporting Directive, while ensuring proportionality to avoid imposing an excessive burden on small and medium-sized companies.[9]

A role for central banks in fighting climate change?

What then, if any, is the role of central banks, and monetary policy in particular, in supporting the transition towards a low-carbon economy?[10]

The starting point for answering this question is the ECB’s primary objective: price stability.

Climate change, if not addressed swiftly, can be expected to affect the economy in a way that poses material risks to price stability in the medium to long term.

On the one hand, the longer the risks of global warming are ignored and policy action delayed, the higher the risks of very large and persistent shocks to output and inflation. So far, most central banks could afford to look through climate-related shocks, mainly because their most visible effects were largely local and temporary.

The coronavirus pandemic demonstrates the challenges central banks are facing in countering large and persistent global shocks, while remaining faithful to their primary mandate. It is with this motivation that we are currently investigating how to integrate climate-related risks into our core macroeconomic models.

On the other hand, the ability of central banks to react to such large shocks may be impaired. Rising temperatures and an increased frequency of natural disasters may further suppress potential output growth and hence the real equilibrium interest rate around which central banks have to calibrate their policies.

Years of subdued inflationary pressure and weak demand have already exhausted the conventional policy space across the industrialised world. And although central banks have successfully relaxed the constraints of the zero lower bound, the risks to financial stability and other side effects emerging from a protracted and intense usage of non-standard measures are likely to rise.

For these reasons, central banks cannot just stand on the sidelines when it comes to climate change. And the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us that monetary and fiscal policies are most effective when they complement each other. This will also be true in the fight against climate change.

I see three major avenues through which the ECB, and central banks more generally, can contribute.

The first is through our involvement in defining rules and standards, and in promoting research for a better understanding of the implications of climate change for financial markets and monetary policy.[11] The ECB is a member of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and has contributed actively to the development of the EU taxonomy of sustainable economic activities. These activities are at the same time instrumental for promoting capital markets union.

The second way in which the ECB can contribute is by ensuring that we ourselves are an environmentally mindful and responsible investor. We are doing this already for our pension fund investments and are now exploring options for other non-monetary policy portfolios.

The third, and most controversial, way in which we can contribute is by taking climate considerations into account when designing and implementing our monetary policy operations.

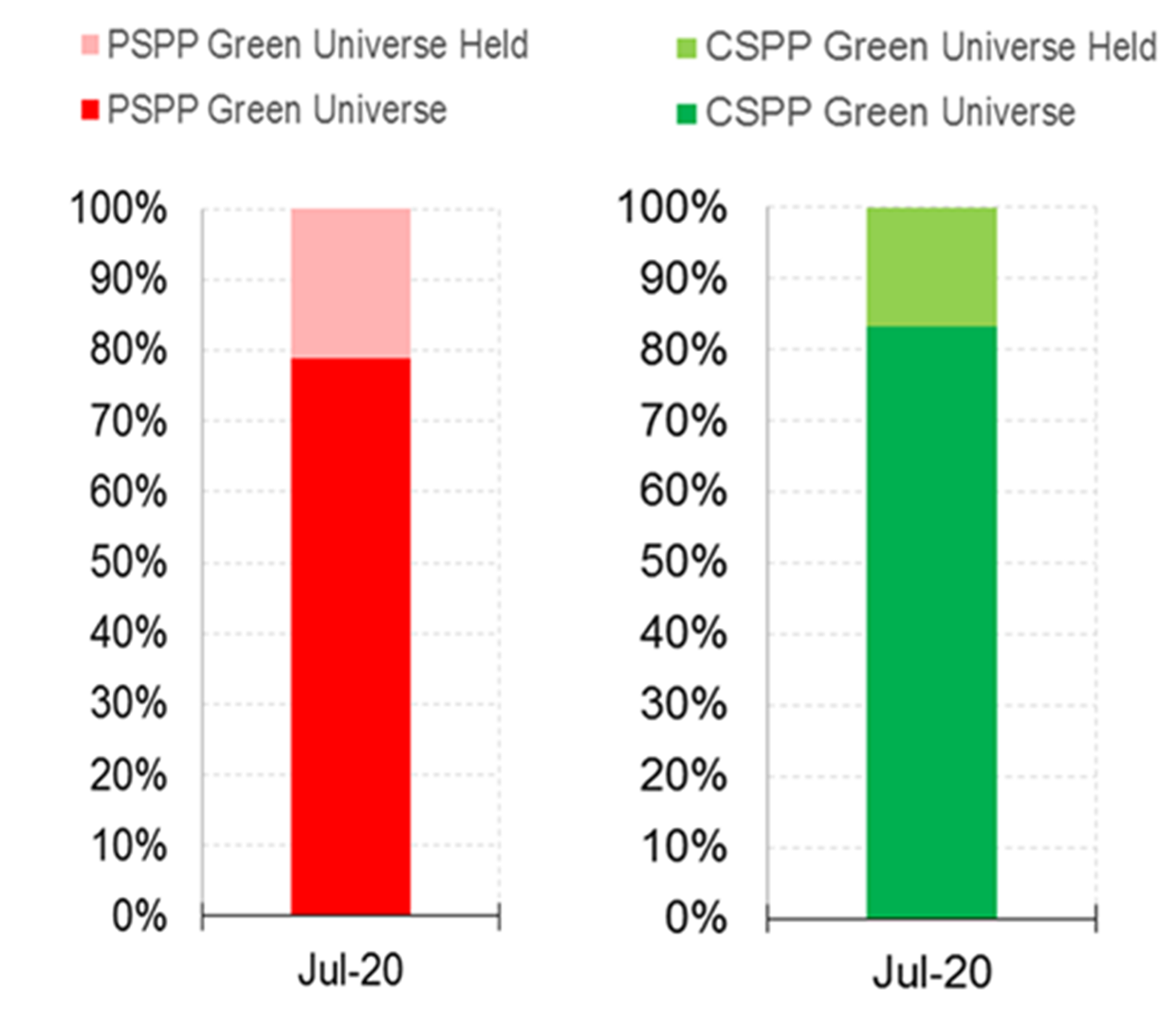

Already now, as part of the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP) and the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), the Eurosystem is buying eligible green bonds. We are currently holding around 20% of the eligible green corporate bond universe (see figure 9).

PEPP and CSPP green eligible bond universe and respective Eurosystem holdings (average since 2018)

Source: EADB, ECB calculations. Last observation: 15 July 2020.

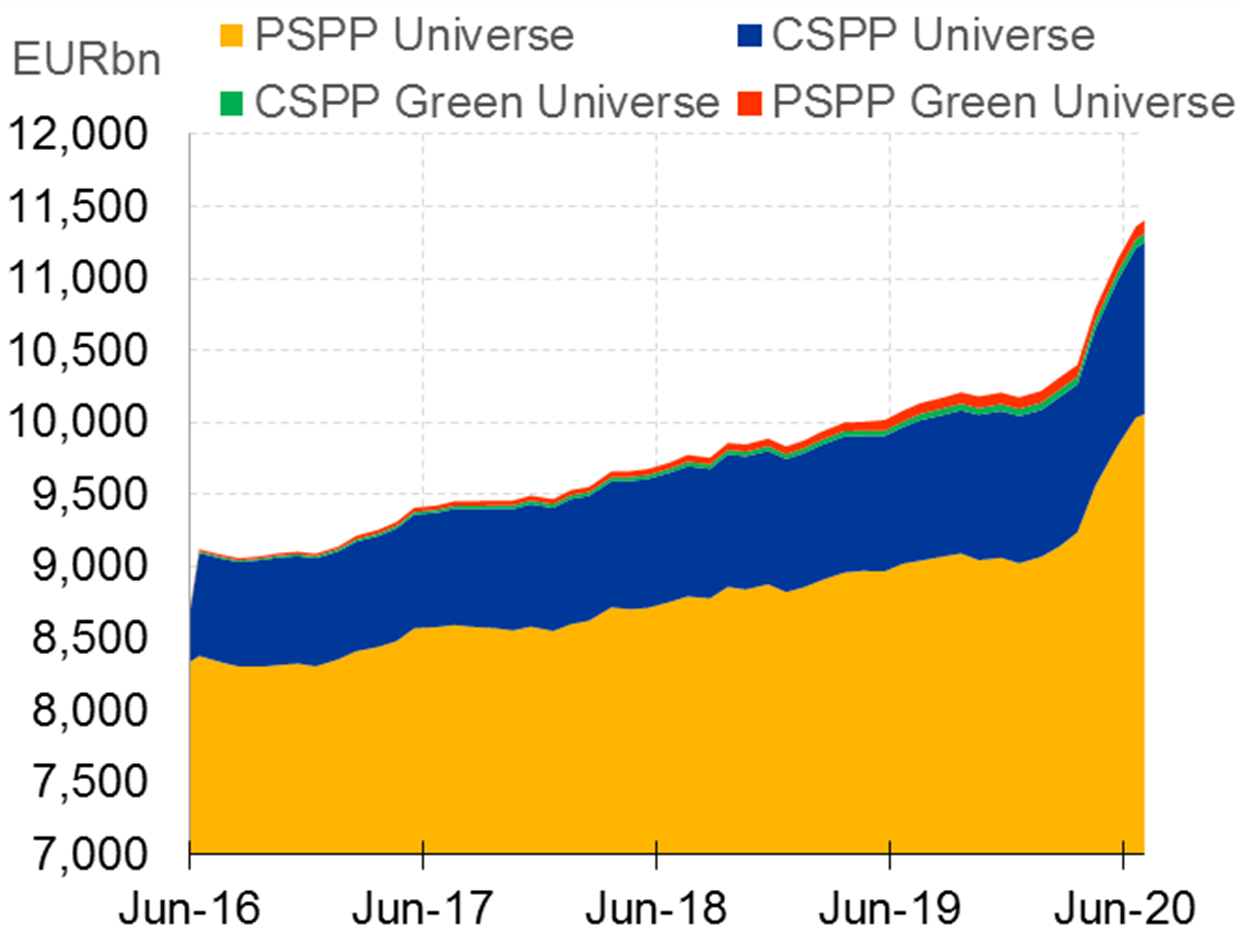

But the green universe only comprises a small fraction of the overall universe (see figure 10). As this market segment grows and develops, the Eurosystem will automatically purchase more green bonds.

PEPP and CSPP universes and respective green universes (in EUR billion)

Source: EADB, ECB calculations. Last observation: 15 July 2020.

The more difficult question, however, is whether the Eurosystem should go beyond current efforts and be more proactive and forceful in greening its asset purchases, or in adjusting the conditions of its refinancing operations, including the collateral framework, to take risks related to climate change into consideration.

For example, we could link the eligibility of securities for our purchase programmes and as collateral in our refinancing operations to the disclosure regime of the issuing firms. Then the Eurosystem would only accept collateral if it is able to fully assess climate-related risks.

These and other questions will feature prominently in our monetary policy strategy review. Without pre-empting the discussion, there are two opposing views regarding the debate on greening asset purchases.

One view is that central banks would overstep their mandate if they were to discriminate among investors on the basis of considerations that fall into the realm of fiscal policy. According to this view, market neutrality is the benchmark central banks should use when purchasing bonds issued by corporates.

The other view is that central banks have to respond to market failures and incorporate the far-reaching risks that climate change poses to price stability when designing their policy instruments.

Importantly, this argument is not about weighing secondary objectives, which may provide additional justifications for monetary policy taking into account climate change. It is about protecting the primary objective.

Of course, central banks would need to be mindful of their effects on market functioning. Overweighting green assets in monetary policy portfolios could crowd out other investors, thereby doing more harm than good.

And while demand can create its own supply, success would ultimately hinge on green issuance growing substantially as the economy transitions towards its new equilibrium.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The current crisis teaches us that decisive and early action is crucial to tackle global disruptions. It enables us to better imagine the much more dramatic consequences that society could face if we were to fail on our efforts to fight climate change. And while the pandemic can eventually and hopefully be cured, global warming is much harder to reverse, raising the costs of taking no action today.

COVID-19 provides a chance to build a greener economy. It is a chance to break the vicious circle of weakening entrepreneurship and the slow diffusion of new and green technologies that have held back productivity growth and prosperity in Europe for too long. And it is a chance to build a deeper and greener financial market that reduces the costs of transitioning towards a low-carbon economy.

The ECB will be no bystander on this journey. As climate change poses severe risks to price stability, central banks are required, within their traditional mandates, to strengthen their efforts to support a faster transition towards a more sustainable economy.

Thank you.

- [1]See Le Quéré et al. (2020), “Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement”, Nature Climate Change, 18 May 2020.

- [2]See UN Environment Programme (2019), Emissions Gap Report 2019. For the 2% goal, the respective number would be 2.7%, which is still very large.

- [3]See Carney, M. (2015), “Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – climate change and financial stability”, speech at Lloyd’s of London, London, 29 September.

- [4]See Samset et al. (20200), “Delayed emergence of a global temperature response after emission mitigation”, Nature Communications, 11.

- [5]See Bayer, P. and M. Aklin (2020), “The European Union Emissions Trading System reduced CO2 emissions despite low prices”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

- [6]See Bravo-Biosca et al. (2016), “What drives the dynamics of business growth?”, Economic Policy, Vol. 31(88), pp. 703–742; and Canton, E. (2016), "Drivers of total factor productivity growth in the EU – the role of firm entry and exit," Quarterly Report on the Euro Area, Directorate General Economic and Financial, European Commission, Vol. 15(1), pp. 25-35, April.

- [7]See De Haas, R., and Popov, A. (2019), “Finance and carbon emissions”, ECB Working Paper No 2318; and Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, March 2020.

- [8]In addition, the sectoral coverage of the taxonomy is still incomplete and needs to be expanded.

- [9]See also Eurosystem reply to the European Commission’s public consultations on the Renewed Sustainable Finance Strategy and the revision of the Non- Financial Reporting Directive, 8 June 2020.

- [10]I focus my remarks on the implications for the conduct of monetary policy. For a recent overview on the supervisory consequences, see Enria, A. (2020), “ECB Banking Supervision’s approach to climate risks”,keynote speech at the European Central Bank Climate and Environmental Risks Webinar, 17 June.

- [11]See, for example, De Haas, R., and Popov, A. (2019, op.cit); Giuzio et al. (2019), “Climate change and financial stability”, Financial Stability Review May 2019; Faria, J. and P. McAdam (2019), “The green golden rule: habit and anticipation of future consumption”, ECB Working Paper No. 2247; Miles, P. (2016), “The impact of disasters on inflation”, ECB Working Paper No. 1982; Lis, E. and C. Nickel (2009), “The impact of extreme weather events on budget balances”, ECB Working Paper No. 1055.

Banca centrale europea

Direzione Generale Comunicazione

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

La riproduzione è consentita purché venga citata la fonte.

Contatti per i media