Disentangling aggregate and sectoral shocks

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 3/2020.

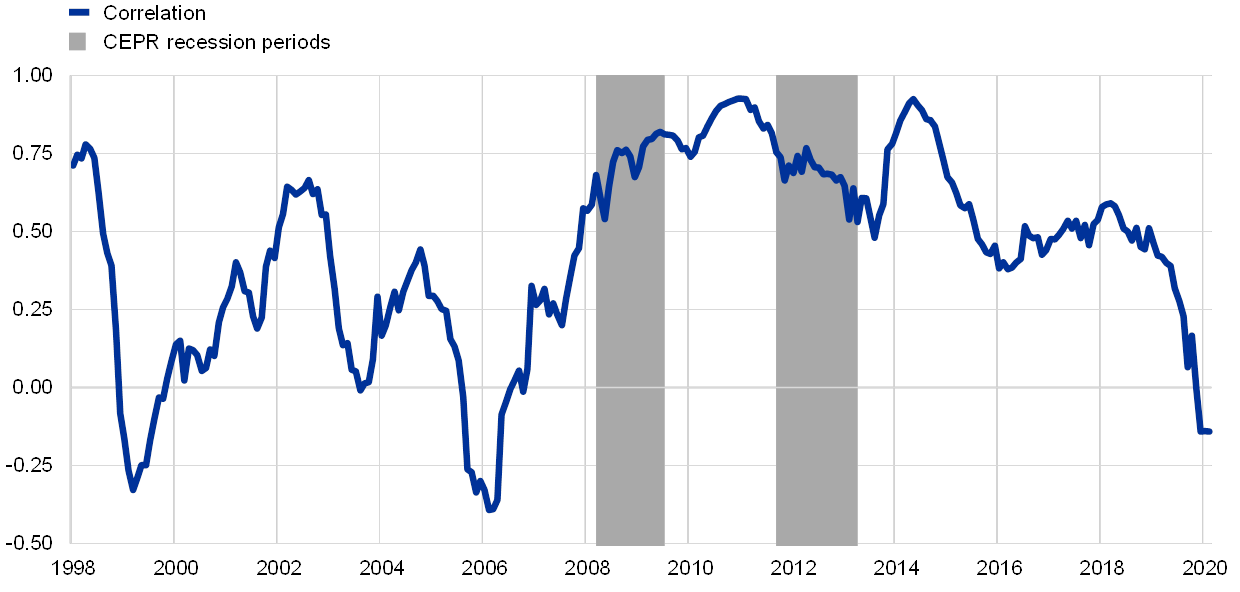

The growth slowdown in 2018-2019 was characterised by a marked divergence of industrial production and retail sales. Activity in both sectors is usually characterised by positive co-movement, particularly during recessions.[1] However, there are also episodes where the correlation between the growth of industrial production and retail sales is low or even turns negative (see Chart A). Despite a strong contraction in industrial production, retail sales barely slowed in 2018-2019. This box uses this co-movement to uncover whether the euro area economy was hit by aggregate or sectoral shocks. It then tries to understand whether these two shocks differ in their impact on output over time. The recent COVID-19 shock is undoubtedly an aggregate shock, hitting industrial production and retail sales simultaneously. Yet its impact on economic activity over time remains uncertain as its characteristics differ substantially from past aggregate shocks.

Chart A

Rolling correlation of industrial production and retail sales

Sources: Eurostat and authors’ calculations.

Notes: The correlation between year-on-year growth in industrial production and retail sales is based on a 12-month rolling window. Grey bars refer to the recession periods as defined by the Centre for Economic Policy Research. The latest observation is for February 2020.

Consumer theory can help to identify aggregate and sectoral shocks. The permanent income hypothesis (PIH) predicts that only unexpected permanent (or persistent) shocks to aggregate income (or production) affect private consumption, whereas transitory shocks do not.[2] At the sectoral level, the PIH implies that transitory shocks should only affect industrial production and not retail sales (i.e. consumption), while permanent shocks should affect activity in both sectors. This difference can be used as a short-run zero identifying restriction in a tri-variate structural vector auto-regression model with retail sales, industrial production and GDP growth.[3]

The identifying assumption is reminiscent of the literature on sectoral and aggregate shocks. Positive co-movement across sectors is not a sufficient condition for a shock to be classified as “aggregate”.[4] Owing to input-output linkages, both aggregate and sectoral shocks can have similar implications for different sectors. In line with a large swathe of the empirical literature, the short-run zero restriction ensures that the conditional correlation between retail sales and industrial production is zero on impact in the case of a sectoral shock to industrial production.[5]

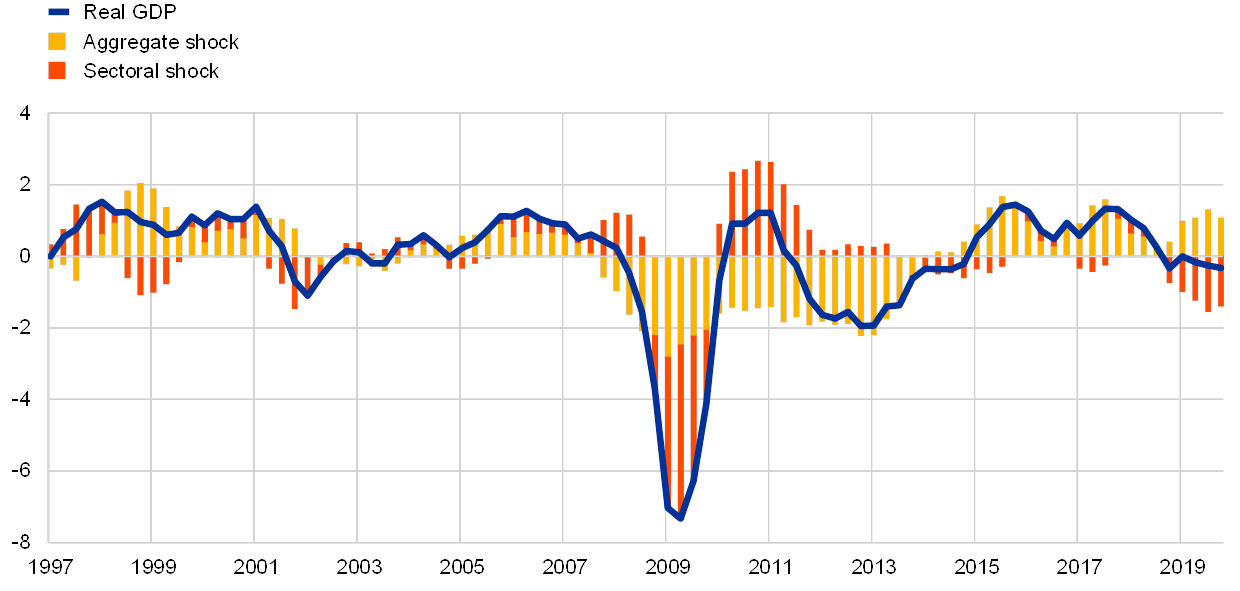

Chart B

Historical decomposition of GDP growth

(year-on-year percentage point deviations from average)

Sources: Eurostat and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Computations based on a tri-variate structural vector auto-regression with retail sales, industrial production and GDP growth using a short-run zero restriction on retail sales. The estimation sample covers the period from the first quarter of 1995 to the fourth quarter of 2019.

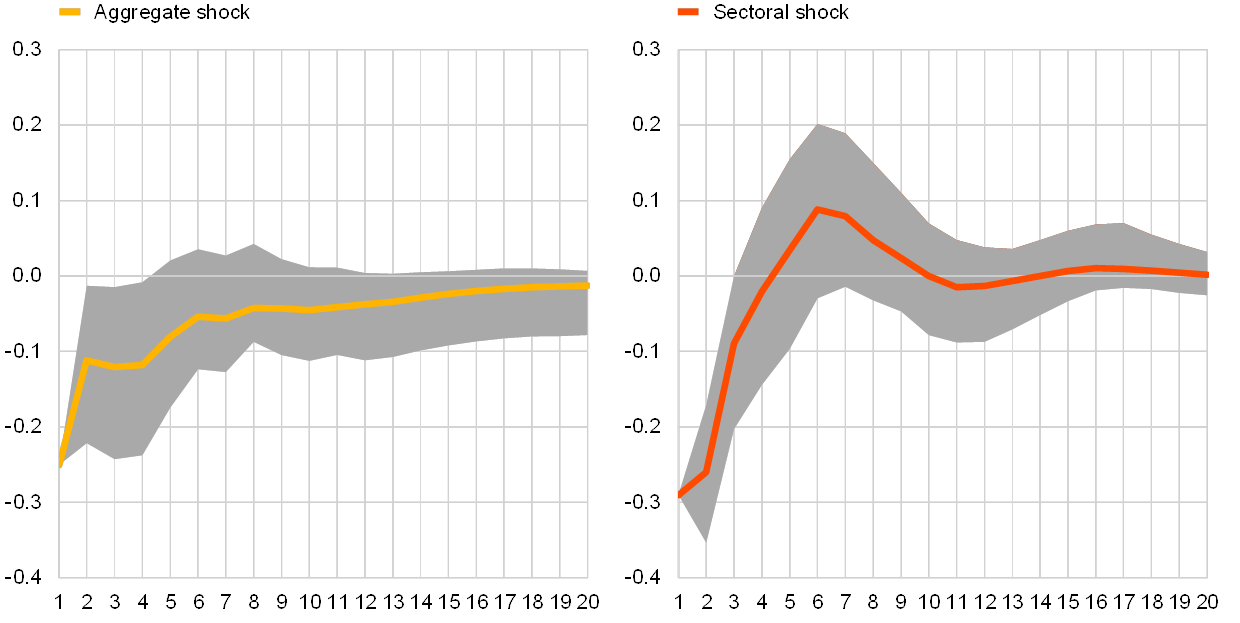

Aggregate shocks have a more persistent impact on economic activity than sectoral shocks. The historical decomposition of GDP in Chart B suggests that most of the 2018-2019 slowdown in GDP growth can be explained by a series of adverse sectoral shocks (e.g. trade tensions and environmental issues in the transport sector). Chart C shows that the response of GDP to aggregate shocks is usually more persistent than its response to sectoral shocks. As GDP growth turns quickly positive after an adverse sectoral shock, this implies that once the (transitory) effects dissipate, industrial production typically converges back to retail sales (and not vice versa).

Chart C

Impulse responses of GDP growth

(percentage point deviation from average; quarter-on-quarter percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Impulse responses reflect a negative shock and are derived from a tri-variate structural vector auto-regression with retail sales, industrial production and GDP growth using a short-run zero restriction on retail sales. The estimation sample covers the period from the first quarter of 1995 to the fourth quarter of 2019. Shaded areas reflect 90% confidence intervals.

The COVID-19 shock differs substantially from a typical aggregate shock. The co-movement between retail sales and industrial production should strengthen again, as both manufacturing and retail sales can be expected to contract from March 2020 onwards. As there are large differences between the characteristics of the COVID-19 shock and those of past aggregate shocks, the above framework is not necessarily well suited to studying the propagation of the COVID-19 shock. In the medium term its impact will depend on various factors, in particular the length of the lockdowns and the effectiveness of the policies mitigating the fallout for households and firms.

- Positive co-movement between retail sales and industrial production plays a prominent role in the NBER’s recession dating procedure. It is also the centrepiece of Burns and Mitchell’s definition of business cycles, see Burns, A. and Mitchell, W., “Measuring Business Cycles”, NBER Studies in Business Cycles, No 2, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1946.

- See also the literature review in Jappelli, T. and Pistaferri, L., “The Consumption Response to Income Changes”, Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 2, 2010, pp. 479-506.

- The weak implementation of the identifying assumption implies that if not all conditions are met for the PIH to hold true (e.g. credit-constrained households leading to excess sensitivity), the timing assumption still allows aggregate and sectoral shocks to be disentangled.

- See Long, J. and Plosser, C., “Sectoral vs. Aggregate Shocks In The Business Cycle”, American Economic Review, Vol. 77, No 2, 1987, pp. 333-336.

- See, for example: Atalay, E., “How Important Are Sectoral Shocks?”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 9, No 4, 2017, pp. 254-280; Foerster, A., Sarte, P.-D. and Watson, M., “Sectoral versus Aggregate Shocks: A Structural Factor Analysis of Industrial Production”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 119, No 1, 2011, pp. 1-38; Forni, M. and Reichlin, L., “Let’s Get Real: A Factor Analytical Approach to Disaggregated Business Cycle Dynamics”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 65, No 3, 1998, pp. 453-473; and Jimeno, J., “The relative importance of aggregate and sector-specific shocks at explaining aggregate and sectoral fluctuations”, Economics Letters, Vol. 39, No 4, 1992, pp. 381-385.