- SPEECH

Societal responsibility and central bank independence

Keynote speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the “VIII. New Paradigm Workshop”, organised by the Forum New Economy

Frankfurt am Main, 27 May 2021

Central banking in times of shifting societal concerns

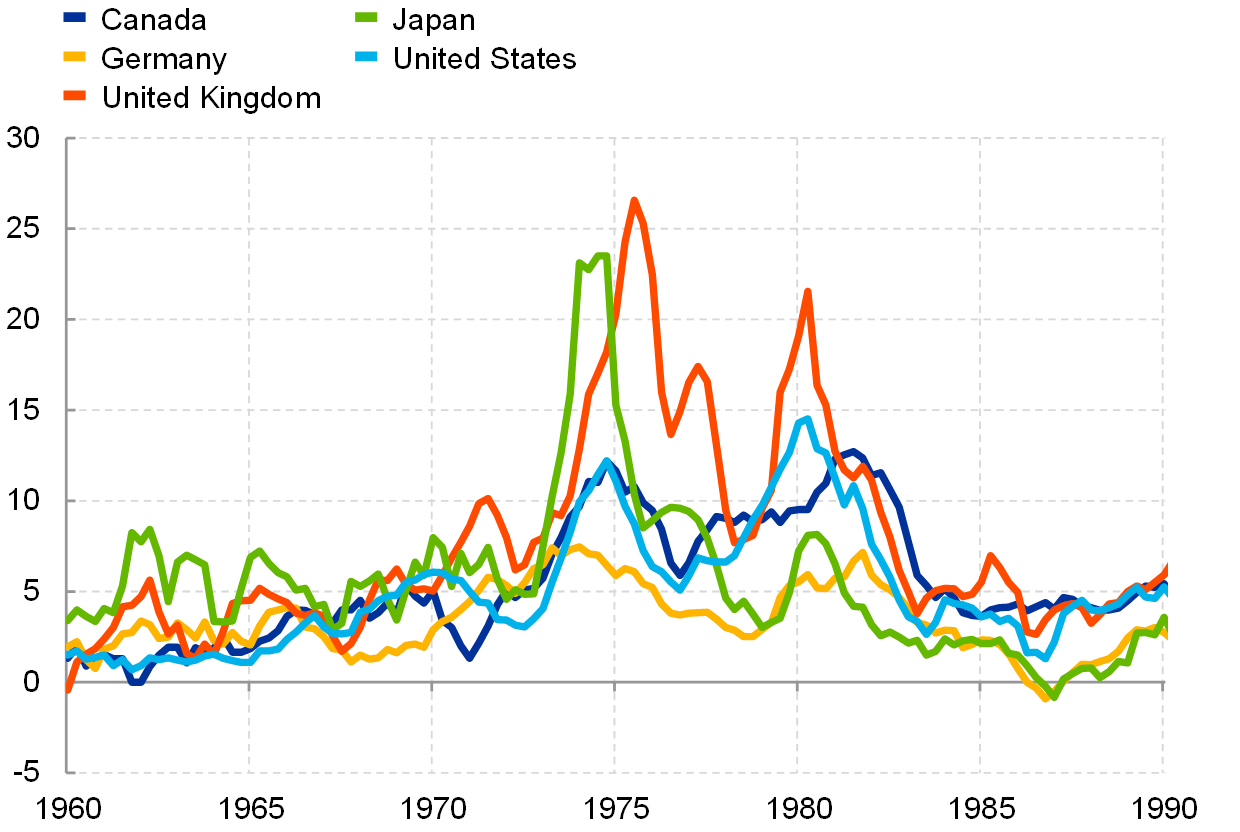

The best contribution that central banks can make to economic prosperity is to maintain stable prices: this was the broad consensus among academic scholars and policymakers emerging in the late 1970s when inflation in many advanced economies had surged to double-digit levels, thereby eroding purchasing power and hitting the poorest in society the hardest (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Consumer price inflation (1960-1990)

(year-on-year change, %)

Source: IMF.

The delegation of the task of maintaining price stability to an independent and accountable institution with a clear mandate has proven successful in solving the underlying time inconsistency problem while upholding democratic principles.

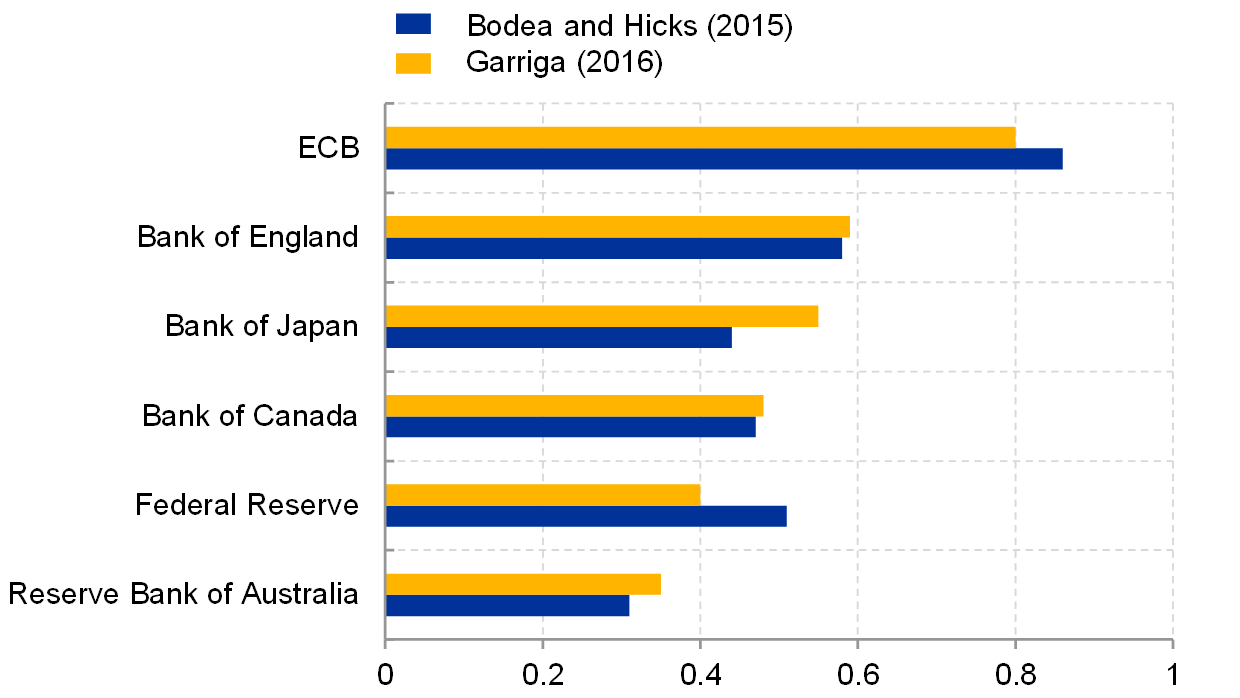

This underpins the large degree of political independence that most central banks enjoy, including the ECB, which consistently ranks as one of the most independent central banks in the world (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Measures of central bank independence

(index, 0-1)

Source: Dall’Orto Mas et al. (2020), “The case for central bank independence”, Occasional Paper Series, No 248, October.

Note: Indices calculated by Bodea and Hicks (2015) and Garriga (2016). Index values in Bodea and Hicks (2015) refer to 2014 (data for the ECB refers to 2010); index values in Garriga (2016) refer to 2012. The values correspond to the unweighted indices of central bank independence. Values closer to 1 indicate higher levels of independence. France, Germany and Italy are excluded from the sample given that the ECB is included.

Yet, many years of low and stable inflation have led to memories fading, particularly among young people, of just how bad a general and persistent rise in the price level can be for society at large. Many young people have never experienced inflation. At the same time, it remains a mystery to many why too low inflation may be as much a concern to society as a period of too high inflation.

Younger generations typically have different concerns and anxieties than price stability: surveys show that they care about climate change and that they fear job uncertainty, having lived through years of crises and now facing the upheaval of the fourth industrial revolution.[1]

These shifts in concerns and preferences have also affected the expectations that many people hold with respect to central banks. In February 2020, the ECB launched its “ECB Listens Portal” to gather feedback from the general public as part of its ongoing monetary policy strategy review.[2]

The (non-representative) results of this listening exercise indicate that many survey respondents assign high importance to the ECB considering issues that go well beyond a narrow interpretation of its traditional price stability mandate.

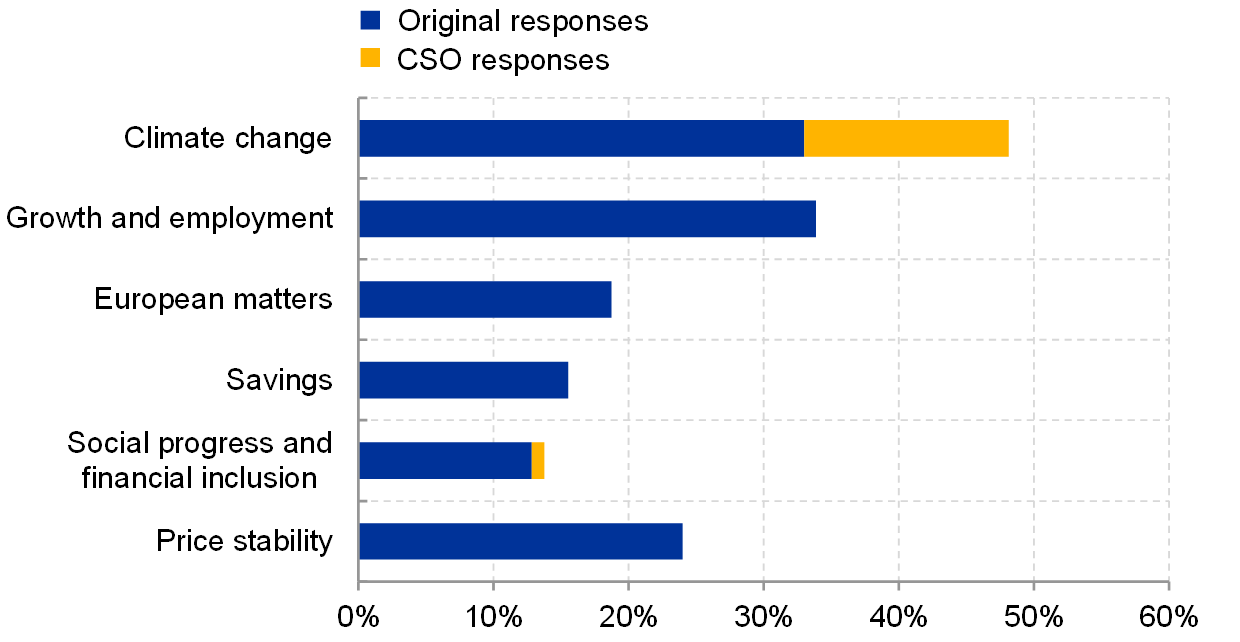

While about a quarter of respondents indicated that the ECB should focus exclusively on price stability and leave other topics to democratically elected bodies, a significant number of respondents expressed the view that the ECB ought to play a more active role in tackling wider societal challenges, with the top priority given to climate change as well as growth and employment (Chart 3).

Chart 3

“ECB Listens” survey: issues that the ECB should consider beyond price stability

(survey responses, %)

Source: ECB Listens portal.

Note: Estimated percentage of respondents in each category (sample size: 3,614). Results calculated by using a dictionary-based approach. Categories are not mutually exclusive. Civil society organisations (CSOs) drew attention to the ECB’s strategy review. Some of these organisations, most notably Greenpeace, called on the public to submit contributions to the ECB Listens Portal, offering standard answers that could be copied into the survey. Overall, around 14% of all responses were copy-paste answers provided by Greenpeace. Another 1% came from other CSOs. As such, original answers amounted to 85% of the sample.

For most people, inflation today is mainly a concern related to asset prices rather than the prices of consumption goods (Chart 4). Our survey suggests that many respondents, especially the younger generations, are particularly concerned about house prices, which are currently not part of the consumption basket that most central banks use to calibrate their policies.

Chart 4

“ECB Listens” survey: Categories of goods and services with the most impactful perceived change in price

(survey responses, %)

Source: ECB Listens portal.

Estimated percentage of respondents in each category (sample size: 3,879). Results calculated by using a dictionary-based approach. Categories are not mutually exclusive. Civil society organisations (CSOs) drew attention to the ECB’s strategy review. Some of these organisations, most notably Greenpeace, called on the public to submit contributions to the ECB Listens Portal, offering standard answers that could be copied into the survey. Overall, around 14% of all responses were copy-paste answers provided by Greenpeace. Another 1% came from other CSOs. As such, original answers amounted to 85% of the sample.

Such shifts in preferences and concerns have not been uncommon in history. Central banks’ mandates, roles and responsibilities have been shaped by history and have changed over time with the preferences of society and their elected representatives, but such changes were always hotly debated.

Granting central banks the power as a lender of last resort, for example, was both controversial and politically contested in the 19th century in the United Kingdom.[3] In the United States, the Federal Reserve was not allowed to lend freely for a long time after it was founded in 1913 even though the United States was one of the most banking crisis-prone economies in the world.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the trade-off between inflation and unemployment dominated public discourse. Many central banks pursued so-called “go-stop” policies: policymakers would only stop stimulating the economy once public concern about inflation started to mount.[4] They would stop raising interest rates when unemployment reached levels unacceptable to political leaders and the broader public.

When Paul Volcker took up the fight against inflation in 1979, he led the US economy into a sharp recession by raising interest rates to more than 20%. A “Wanted” poster featured him and six of his colleagues at the Federal Reserve Board. A magazine accused him of “premeditated and cold-blooded murder of millions of small businesses”.[5]

Volcker ultimately succeeded in bringing down inflation and in paving the way for a sustained period of economic prosperity. He proved that a determined and independent central bank can bring long-lasting gains to society by taking the heat and thereby gaining the trust and confidence of the public.

Facing the challenges of today

Central banks today need to exhibit the same degree of persistence, courage and commitment.

As much as Volcker repeatedly and tirelessly warned of the risks of too high inflation, central banks today need to explain, over and over again, why long periods of too low inflation are just as much a problem to society.

If a large share of society tends to underestimate the perils of low inflation, then there is the risk of a gradual loss of support, trust and confidence in the actions of central banks.

This risk is particularly acute if the actions are as far-reaching and complex as they have been over the past decade.

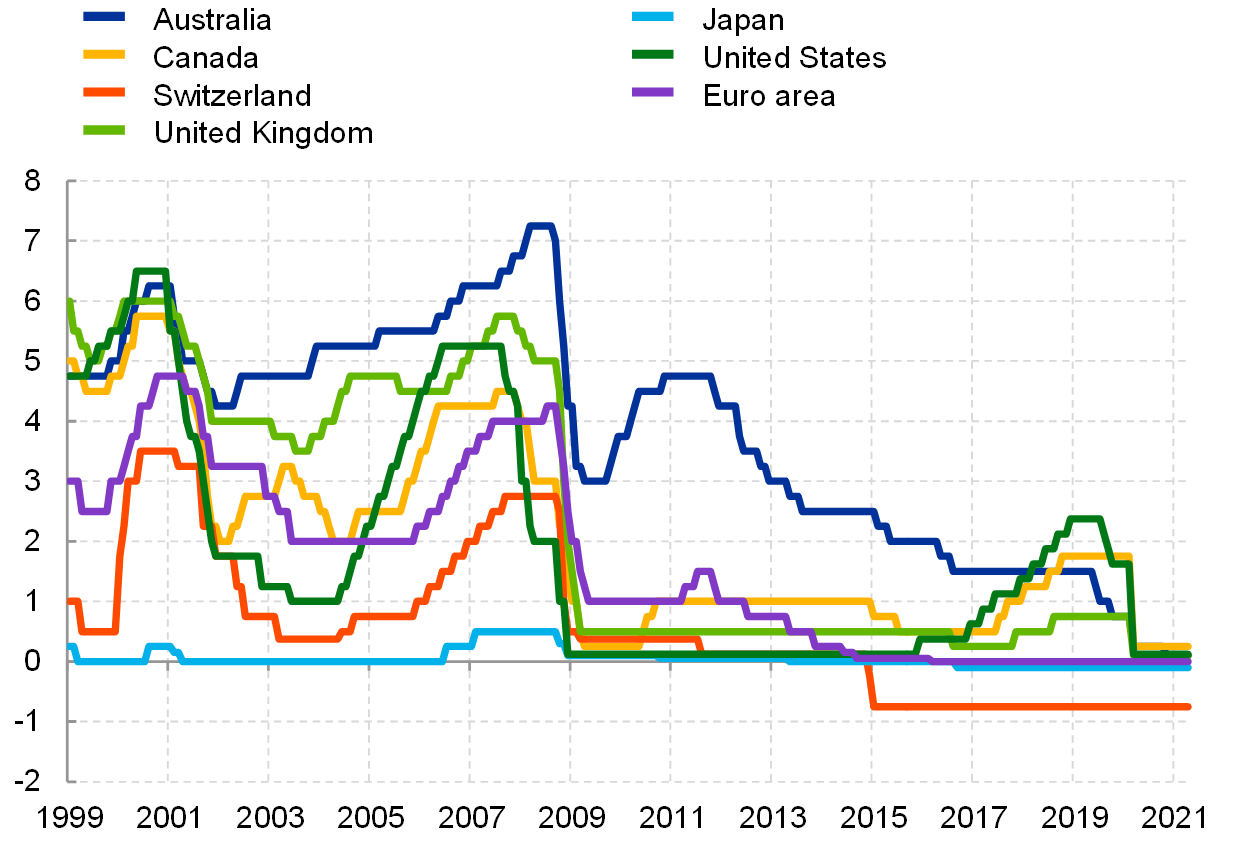

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, a combination of adverse structural and cyclical factors jointly contributed to the rapid erosion of central banks’ conventional policy space (Chart 5).

Chart 5

Central bank policy rates

(%)

Source: BIS.

Note: The policy rate for the euro area refers to the main refinancing operation (MRO).

As a result, central banks were forced to expand the set of instruments used to achieve their mandates.

In the euro area, there is broad agreement among experts that asset purchases, targeted longer-term refinancing operations, forward guidance and negative rates were necessary to shelter the economy from the otherwise devastating consequences that years of subdued demand would have meant for employment, wages and prices.

But these measures, and their broader transmission channels, are hard to understand even for experts. They remain inaccessible for a large part of society, in spite of all the efforts of central banks to communicate on their policies. As Andy Haldane put it: “… around 95% of all the words central banks utter are inaccessible to around 95% of the population.”[6]

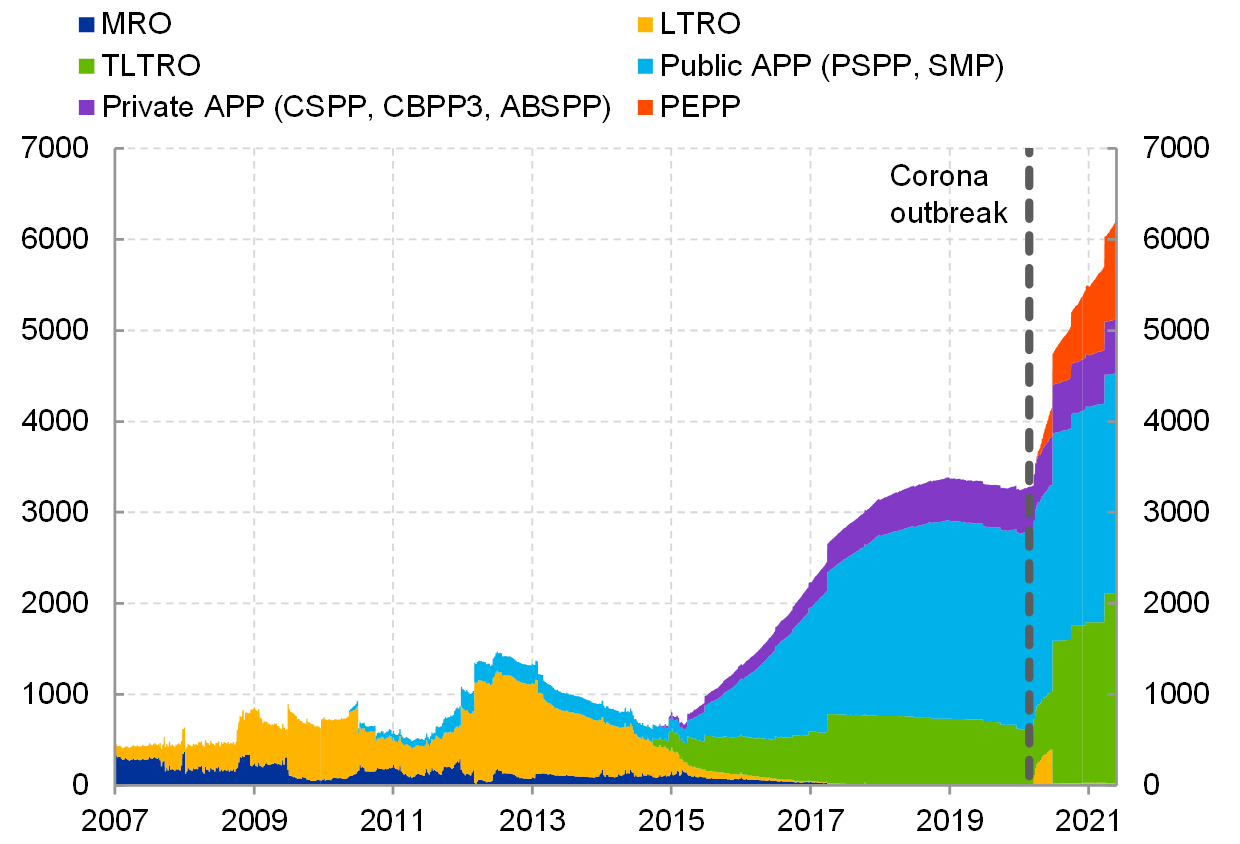

The sheer numbers involved in today’s central bank operations intimidate many people, and feed perceptions that central banks have become more powerful than ever, and potentially too powerful. The size of the ECB’s balance sheet, for example, has expanded rapidly in recent years (Chart 6).

Chart 6

Evolution of ECB balance sheet

(€ billion)

Source: ECB, ECB calculations.

Latest observation: 25 May 2021.

And if people do not understand what we do, they may not trust us that we are doing the right thing. Data from the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey corroborate this view. They confirm that a better understanding of the ECB’s tasks is positively correlated with trust in the institution (Chart 7).

Chart 7

ECB knowledge and trust in the ECB

(x-axis: index, 0-7; y-axis: index, 0-10)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey.

Note: Data as of May 2020. Data takes country-level differences into account. With respect to ECB knowledge, respondents were asked to assess the correctness of seven statements about the objectives and responsibilities of the ECB. ECB knowledge is computed as the total number of correct responses out of seven statements. Negative values and values above 7 are due to the netting out of country-specific effects. Self-reported trust in the ECB is measured over an 11-point scale from 0 (no trust at all) to 10 (trust completely).

However, according to the Eurobarometer, public trust in the ECB declined notably as of 2008, although trust in the euro remained broadly stable even at the time of the euro area sovereign debt crisis (Chart 8). Only recently trust has started to recover from very low levels.

Chart 8

Trust in the ECB and support for the euro

(net trust, net support)

Source: Eurobarometer, own calculations.

Notes: Net support for the euro is calculated as the share answering “for” minus the share answering “against” to the question “Please tell me whether you are for or against it: A European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro.” Net trust is calculated as the share of respondents giving the answer “Tend to trust” minus the share giving the answer “Tend not to trust” to the question “Please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?: The European Central Bank.” Respondents who answered “don't know” are excluded in both cases.

Latest observation: Winter 2020/2021.

Heated public debates about the broader distributional and societal consequences of unconventional policy measures are testimony to the looming distrust facing central banks today.[7]

For example, since financial wealth is distributed unevenly in society, some argue that measures that are focused on boosting asset prices disproportionally favour the rich. Similarly, purchases of corporate bonds have ignited a discussion whether central banks should continue to purchase bonds issued by firms with a large carbon footprint.

Independent central banks cannot simply turn a deaf ear to the concerns of the public. Public trust is essential for the successful conduct and implementation of monetary policy.[8]

More so, independence requires a central bank to respond to the concerns of the public and to carefully evaluate whether and how it may be able, within its mandate, to respond to these concerns.

A failure to do so would risk nurturing what Yascha Mounk once labelled “undemocratic liberalism” – a system in which citizens feel that their political preferences are routinely ignored by unelected authorities.[9]

In a democracy, people have the power to express their discontent with the government at the ballot box. But they cannot elect a new central bank leadership.

Independence therefore carries large responsibility. And central banks are taking this responsibility seriously.

For example, most experts agree that central banks do not have the tools to address inequality. But the absence of tools does not free central banks from carefully examining the distributional consequences of unconventional policy measures, and from taking such findings into account when weighing and calibrating policy options.

At the ECB, for example, staff have found that asset purchases tend to compress rather than widen income distribution because of the positive employment effects of lower interest rates, while the effects on wealth inequality are negligible.[10]

Colleagues at Sveriges Riksbank recently found that, in Sweden, expansionary monetary policy increases the total incomes of the poorest and richest individuals but less so for middle-income households.[11]

Further analysis is needed to better inform central banks’ internal as well as public debates about the effects of monetary policy on inequality.

Central banks and climate change

Similarly, a frank, open and constructive debate is needed as to whether and how central banks can support a faster transition to a greener economy – a demand that almost half of all respondents in our ECB listening events identified as a societal challenge that the ECB should consider in its monetary policy.[12]

Climate change is without doubt one of the most pressing policy issues confronting policy makers at the global level. The EU has declared the European Green Deal – the plan to make the EU’s economy sustainable – one of its top priorities.

The Treaty unambiguously assigns the primary responsibility for climate policies to the European Parliament and the Council – not the ECB.[13] In other words, in order to observe the principle of institutional balance, any measures the ECB were to take must not encroach upon the powers of other European institutions or impede their effectiveness.

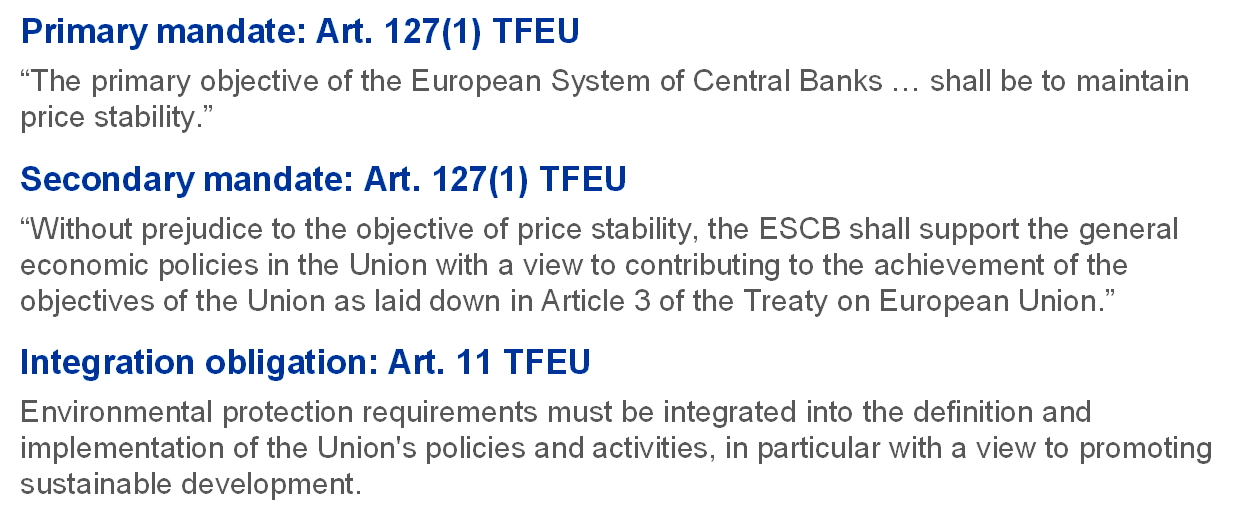

The ECB’s objectives are clearly spelled out in the Treaty and cannot be changed without also changing the Treaty itself.[14] These objectives define the scope and the limits of our potential actions in all areas.

When it comes to climate change, our potential role could be based on both our primary and secondary objectives.

Under our primary mandate, the ECB must take climate change into account if this is a prerequisite for maintaining price stability (Chart 9).[15]

Chart 9

The obligation to act according to the Treaties

The extent of the risks to price stability from climate change is subject to an intense and growing debate, and the question is far from settled.

Critics argue that the risks of climate change to price stability remain far out in the future, and that it would be highly unusual for a central bank to take pre-emptive action to shocks that have not yet materialised.

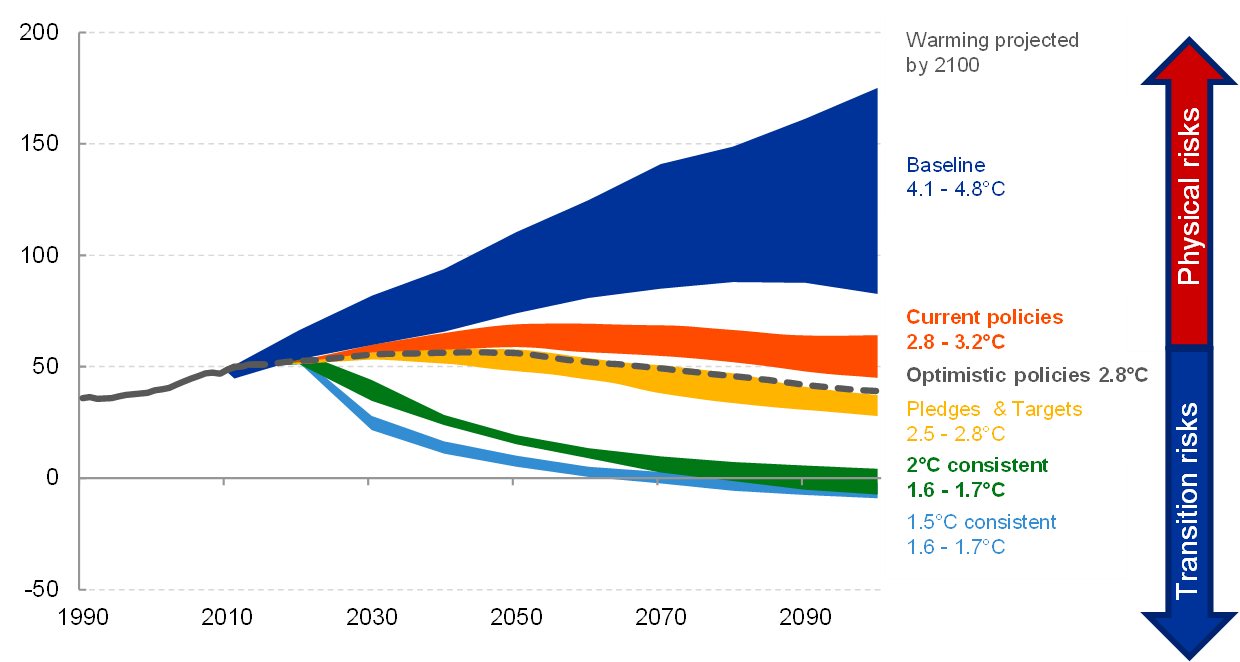

Proponents, on the other hand, argue that global warming causes exceptionally large and partly irreversible changes to our economies. Global emissions are not projected to fall over the next 40 years even assuming that all currently planned climate policies are implemented (Chart 10).

Chart 10

Climate risk scenarios: projections of carbon emissions and global warming

(emissions of CO2, gigatonnes per year)

Source: Climate Action Tracker, Warming Projections Global Update (projections: December 2019).

In the absence of a faster acceleration towards a low-carbon economy, it would be a question of when rather than if climate change will affect price stability. The effects on potential growth and financial stability could be so large that it would leave central banks with few options to fulfil their primary mandates.

Proponents therefore argue that such exceptional risks require central banks to be forward-looking to reduce both the probability and severity of future shocks to inflation.

Under our secondary mandate, the ECB has the obligation – indicated by the legal term “shall” – to align its monetary policy measures with the general economic policies of the EU, as long as this does not prejudice our price stability objective (Chart 9).

This implies, among other things, that if the ECB is faced with two policy options that are equally effective with respect to its primary objective, it must choose the one that is better aligned with the EU’s economic policies.

Purchases of corporate bonds vividly demonstrate this principle.

Given the high priority that European policymakers attach to climate protection, if purchases of two bond portfolios are deemed to provide a similar degree of monetary accommodation, but one of them has a lower carbon footprint, then the ECB should purchase the portfolio with the lower footprint.

That is, the ECB is free to choose the instrument – in this case, asset purchases – but it needs to calibrate its use in line with the objectives set out in the Treaty.

In addition, the Treaty specifies that environmental protection requirements must be incorporated into the definition and implementation of the ECB’s monetary policy – the “integration obligation” (Chart 9).

Any policy action on the part of the ECB must also respect the general provisions of EU primary law, including the principles of proportionality and an “open market economy”. These principles impose additional constraints on the ECB’s potential actions in the area of climate change.

For example, adjustments to our asset purchase programmes or the collateral framework, such as strict exclusion policies[16] or more subtle “tilting” strategies[17], would have to be checked against these general principles.

One area of contention in the debate about climate policies is whether the market is an appropriate benchmark if markets, by themselves, do not lead to an efficient allocation of resources, as is currently the case owing to the presence of environmental externalities.

Currently, private sector assets are purchased in accordance with the “market neutrality” principle, which implies that those firms that issue more bonds tend to benefit more from our asset purchase programmes, ignoring broader portfolio rebalancing effects.

In other words, the “market neutrality” principle disregards any malign welfare effects that may arise if those that issue more bonds have a larger carbon footprint. It may therefore directly counteract efforts by the Union to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and accelerate the transition towards a green economy.

Taken together, therefore, our mandate requires a careful assessment of the extent to which the ECB can and should “green” its monetary policy operations. This is what we are currently doing under our monetary policy strategy review.

What can be said with reasonable confidence at this stage is that concerns over potential “mission creep” are misplaced: the Treaty not only allows but requires the ECB to take climate change into account.[18]

In doing so, we have to find the right balance between exploring what is feasible within our mandate and ensuring that our actions never interfere with our primary objective of price stability. After all, the fight against climate change requires structural measures that monetary policy as a cyclical tool cannot provide. Finding this balance holds the promise to enhance public trust and ultimately safeguard our independence.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The challenges central banks are facing today are fundamentally different from the ones that were relevant when they gained broad political independence. Inflation is less of a concern to many people, in large part reflecting the achievements of central banks over time.

As a result, expectations towards central banks have changed. Many call for central banks to have a more active role in tackling wider societal challenges, climate change in particular. Such shifts in preferences coincide with a broad distrust of far-reaching and complex monetary policy measures taken by central banks in recent years to protect the economy from a perilous spiral of falling prices and wages.

In this environment, the demands on central bank communication are enormous. Independent central banks have a duty to respond to the concerns of the public and to carefully evaluate whether and how they may be able, within their mandate, to respond to these concerns. Accountability is the quid pro quo of independence.

The ECB is doing this diligently as part of its ongoing monetary policy strategy review. We are analysing the effects and side effects of our unconventional monetary policy instruments in depth. And we are exploring if and how, within our mandate, we can contribute to the broader objectives of the Union, including by taking measures that will help accelerate the transition towards a more sustainable economy, while firmly adhering to our primary objective of price stability.

Thank you for your attention.

- See, for example, The Deloitte Global Millennial Survey 2020.

- Various listening events, both with experts and with the general public, were held by the ECB and the Eurosystem’s national central banks between October 2020 and February 2021. An overview of the NCB’s listening events is provided on the ECB website.

- See, for example, Calomiris et al. (2016), "Political foundations of the lender of last resort: A global historical narrative," Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 28(C), pp. 48-65.

- See also Goodfriend, M. (2007), “How the world achieved consensus on monetary policy”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (4): pp. 47-68

- Treaster, J. (2005), “Paul Volcker: The Making of a Financial Legend”, John Wiley & Sons.

- See Haldane, A. (2018), “Climbing the Public Engagement Ladder”, speech at the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), 6 March.

- See also Schnabel, I. (2020), “Narratives about the ECB’s monetary policy – reality or fiction?”, speech at the Juristische Studiengesellschaft, Karlsruhe, 11 February.

- See, for example, Christelis, D., Georgarakos, D., Jappelli, T. and van Rooij, M. (2020), “Trust in the central bank and inflation expectation”, Working Paper Series, No 2375, European Central Bank; Mellina, S. and Schmidt, T. (2018), “The Role of Central Bank Knowledge and Trust for the Public’s Inflation Expectations”, Discussion Paper, No 32, Deutsche Bundesbank.

- See Mounk, Y. (2016), “Illiberal Democracy or Undemocratic Liberalism?”, Project Syndicate, 9 June.

- See Lenza, M., and J. Slacalek (2018), “How Does Monetary Policy Affect Income and Wealth Inequality? Evidence from Quantitative Easing in the Euro Area,” Working Paper Series 2190, European Central Bank; and Dossche et al. (2021), “Monetary policy and inequality”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 2/2021.

- See Amberg, N, T Jansson, M Klein and A Rogantini Picco (2021), “Five Facts about the Distributional Income Effects of Monetary Policy”, Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper No. 403.

- The figure includes survey respondents who used standard responses provided by Civil society organisations (CSOs). Excluding the standard CSO responses submitted, over 30% of survey respondents identified climate change as a policy issue that the ECB should consider.

- Article 192 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) provides that the Union legislator, i.e. the European Parliament and the Council, is competent to decide what action should be taken by the Union to achieve the objectives of preserving, protecting and improving the quality of the environment and promoting measures at international level to deal with environmental problems, in particular combatting climate change.

- See, for example, Issing, O. (2000), “Monetary policy in a new environment”, speech at a BIS Conference on “The new monetary policy environment”, Frankfurt am Main, 29 September.

- For a related speech, see Schnabel, I. (2021),“From green neglect to green dominance?”, 3 March.

- See Greenpeace (2021), “Greening the Eurosystem collateral framework”, March.

- See Schoenmaker, D. (2021), “Greening Monetary Policy”, Climate Policy, January.

- See also Elderson, F. (2021), “Greening monetary policy”, The ECB Blog, 13 February.

Europos Centrinis Bankas

Komunikacijos generalinis direktoratas

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurtas prie Maino, Vokietija

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Leidžiama perspausdinti, jei nurodomas šaltinis.

Kontaktai žiniasklaidai- 27 May 2021